int('25') + 227Reading: Think Python Chapter 3, Chapter 6.1-6.3

Functions are pre-defined sequences of instructions. Like variables, functions have names, and functions must adhere to the same naming convention. We can call a function with the following syntax:

None is returnedUnless you define a function called function_name() when you run the code above, you’ll get an error.

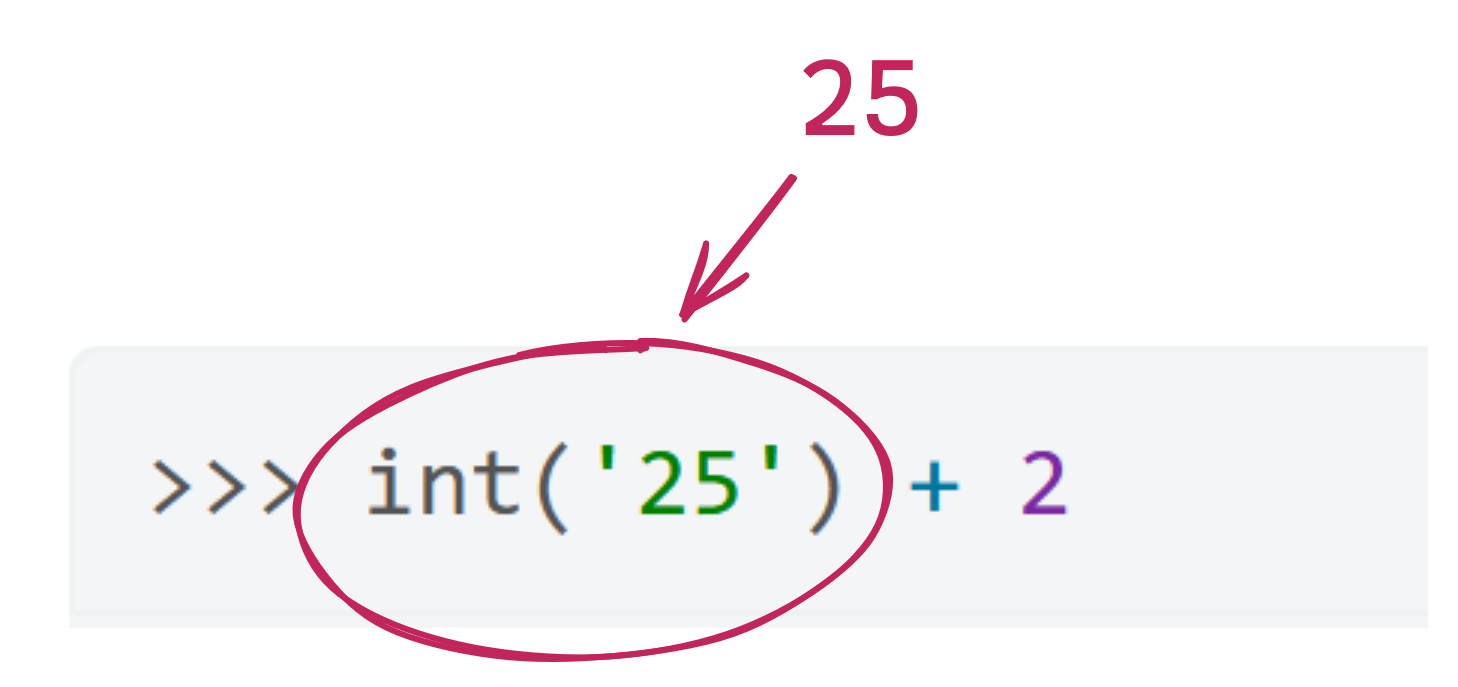

Functions can form parts of expressions:

Since int('25') returns the integer 25, after the function call, this is equivalent to:

Expressions can form the arguments of function calls:

The expression '2' + '5' is evaluated before the function call. It is inside the parentheses of the call, and function call parentheses respect order just as expression parentheses do.

After the evaluation, the result becomes int('25') + 2, identical to the first example. As always, these intermediate steps will never be shown to us by Python, but it’s important to understand how the programming language works.

There is no limit to how deep you can nest function calls and expressions:

In practice, however, writing and reading this sort of deeply-nested function call is difficult, and unnecessary. Instead, use variables:

Python comes with a built-in module, math, for simple mathematical functions. The module comes with functions and variables.

To import a module, use the import keyword, followed by a space, followed by the module name:

You only need to do this once in the interpreter, or once at the beginning of a program you write in the editor.

After importing the module, you can use its functions:

Note the syntax: there is a dot in between the module name math and the name of the function: this indicates to Python that the function is associated with the module.

Modules can also include variables; one example from math is math.pi, a good approximation of \(\pi\):

Like everything you’ve seen so far, these functions and variables can be composed into expressions. We’ll start with a simple expression:

This expression can form the argument of a function:

That expression can be combined with other functions or operators into a more complicated expression:

There’s no technical limit to how complicated this can get:

There is almost never a need to make an expression as complicated as the one above.

Here is the same result composed with variables. This is easier to do using the editor than the interpreter. It uses more lines of code, but achieves the same result.

equivalent.py

For important examples, you can trace through (and edit) the code directly within these course notes.

Note that the program written in the editor requires a print statement to have output:

Beyond built-in functions and functions from modules, Python lets us define our own functions. This allows us to write code once and execute it many times.

The function definition introduces new syntax:

def (“define”):) afterwards

You will see many more examples of this kind of syntax, with a controlling statement, a colon, and an indented block. The indentation groups a block of code with the controlling statement. It says that everything indented belongs to, and is controlled by, the function definition (in this case).

If we run the simple_function.py program above (try it), there will be no output. We have defined the function, but we have not called it.

Calling a user-defined function is the same as calling a built-in function: use the function name, followed by parentheses.

Note that the function call occurs outside of the indented block of the function definition, and remember that while the function definition does not do anything by itself, you must define a function before using it (if it isn’t a built-in function like str() or print()).

NoneWe haven’t specified a return value for the function, so it returns nothing. In Python, “nothing” is represented by a special variable called None. It isn’t zero, it isn’t the string 'None', it’s nothing.

Trace the execution of this program:

simple_function_call.py

Three things are printed because there are three print statements:

= on line 4 is evaluated

int(40.1) returns int 40ii is printed= on line 6 is evaluated

hello_world()'Hello, world.' is printed by the function callNoneNone, is assigned to jj is printedTrace through this program, modify it, understand it. Ask questions if you have them.

It’s a short program, but it demonstrates several concepts that are fundamental to what we will learn in the future.

print() is a built-in function that returns None in addition to creating output at the console.

To demonstrate, let’s assign the return from print to a variable:

The print statement still creates the output we expected. If we print what was returned:

We have called built-in functions with arguments, such as int(40.1). We can also define functions that take arguments:

simple_function_call.py

Trace through the execution. Note how variable v is internal to the rounder function. Each time the function is called, \(v\) takes a different value.

Defining your own functions, especially functions that take arguments, is a powerful part of code reuse. Code reuse makes programming extremely powerful: you can write instructions once, and execute them many times, running them with different inputs to get different outputs.

returnWe have seen built-in functions that return a value after evaluation, such as float:

We have also seen how print does not return anything (None):

We have also written our own functions, so far without returning anything:

Calling the function results in the print statement running (and printed output). However, nothing is returned.

return ValuesWe can write functions so that they do return something. This is one of the most powerful concepts in computer programming.

To make your function return a value, use the keyword return at the end of the function:

When execution inside a function reaches a return statement:

return value is brought back to the function call

Note that nothing is printed by the function itself!

dprint on line 6Write a function fixed_sequence that takes no arguments and prints the following when called:

1 2 3 4Begin with this “starter code.”

practice1_3_4.py

Keep the two function calls: when you have written the body correctly, the program should print:

1 2 3 4

1 2 3 4Write a function variable_sequence that takes one argument, an integer, and prints out that integer and the next three consecutive integers in sequence:

variable_sequence(1) results in printed 1 2 3 4variable_sequence(2) results in printed 2 3 4 5variable_sequence(4) results in printed 4 5 6 7Begin with this “starter code.”

practice1_3_5.py

Keep the function calls: when you have written the body correctly, the program should print:

1 2 3 4

2 3 4 5

4 5 6 7Write a function return_sequence that takes one argument, an integer, and returns a string consisting of that integer and the next three consecutive integers in sequence:

return_sequence(1) results in returned string '1 2 3 4'return_sequence(2) results in returned string '2 3 4 5'return_sequence(4) results in returned string '4 5 6 7'Write a function doubler that takes one argument, a float, and returns the float multiplied by two.

Write another function halved that takes one argument, a float, and returns the float divided by two.

When you’re done, the same function should return its argument:

(All of these functions should be in the same .py file)

Get more practice with the functions worksheet

Homework problems should always be your individual work. Please review the collaboration policy and ask the course staff if you have questions. Remember: Put comments at the start of each problem to tell us how you worked on it.

Double check your file names and printed output. These need to be exact matches for you to get credit.

Submit all homework files as a .zip file to the submit server.

If you are stuck, post on Ed or go to office hours for help.

Write a function squared_root that takes one argument, an integer, and prints out that integer, its square root, and its square, and the integer again, in sequence, with a single space in between each:

squared_root(1) results in printed 1 1 1 1squared_root(4) results in printed 4 2 16 4squared_root(0) results in printed 0 0 0 0You can expect the argument will always be positive integer that is a perfect square.

Begin with this “starter code.”

squared_root.py

Once the function is working, remove the function calls, and keep only the function definition. Submit as squared_root.py.

Hint: You can use the str() function to convert any numeric value into a string, and the + operator between strings to concatenate (join) them.

The program below is intended to implement the reverse_sequence function:

reverse_sequence(6) should print 6 4 2 0reverse_sequence(3) should print 3 1 -1 -3reverse_sqeuence.py

Fix/complete the function so that it works as intended. Submit as reverse_sequence.py.

This program will contain two functions.

Write one function, hello_world that simply prints Hello, world!.

Write a second function, call_hello_world that contains a function call to the first hello_world function.

call_hello_world.py

When finished:

Hello, world!hello_world) should change the output of the call to the second function

Before submitting, delete the call to call_hello_world. Keep the definitions. Submit as call_hello_world.py.

Write a function time_convert that converts from seconds to days. It should truncate at five digits after the decimal. Output should print in the following format:

time_convert(500) prints 500 seconds is 0.00578 daystime_convert(2000) prints 2000 seconds is 0.02314 daysSubmit as time_convert.py

There are 60 seconds in one minute. There are 60 minutes in one hour. There are 24 hours in one day.

You can truncate by:

math.floor on the resultThe factor of ten you choose (10, 100, 1000, etc.) will determine the decimal place of the truncation.

Write a function time_convert_return that performs the same conversion as the previous problem, but instead of printing the output, it returns a string:

time_convert_return(500) returns string '500 seconds is 0.00578 days'time_convert_return(2000) returns string '2000 seconds is 0.02314 days'Note: The quotes around the string return values indicate that a string is returned: the string itself should not include these quotes.

Submit as time_convert_return.py

There are 60 seconds in one minute. There are 60 minutes in one hour. There are 24 hours in one day.

You can truncate by:

math.floor on the resultThe factor of ten you choose (10, 100, 1000, etc.) will determine the decimal place of the truncation.