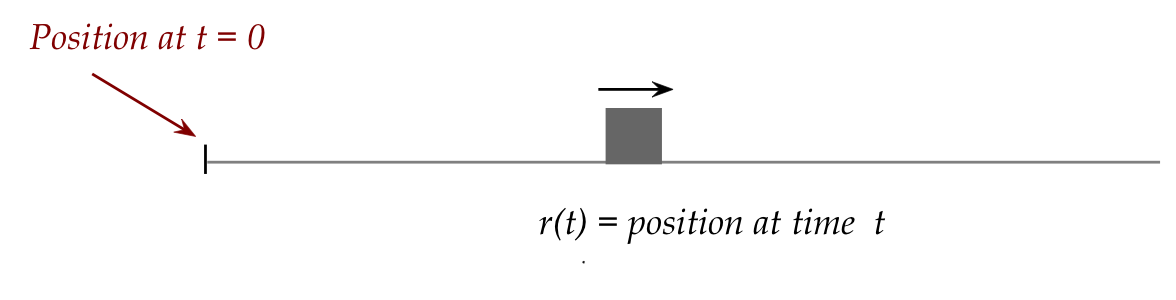

- Experimental results (Galileo) show that the velocity increases over time as the block proceeds downwards.

- This is where Newton made his key insight: velocity is the instantaneous rate of change of distance: $$ v(t) \eql \frac{dr(t)}{dt} \eql x^\prime(t) $$

- And because velocity is itself changing, it's fair to ask: what is $$ a(t) \eql \frac{dv(t)}{dt}? $$

- This is the kind of thing that has the potential of becoming a law: nature is such that acceleration is constant.

- A more refined theory will account for gravity that pulls objects downward and is stronger the closer you get to the bottom of the incline, meaning \(\frac{da(t)}{dt} \neq 0\).

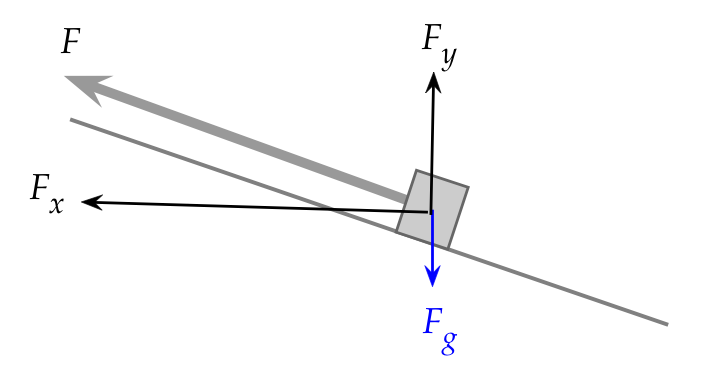

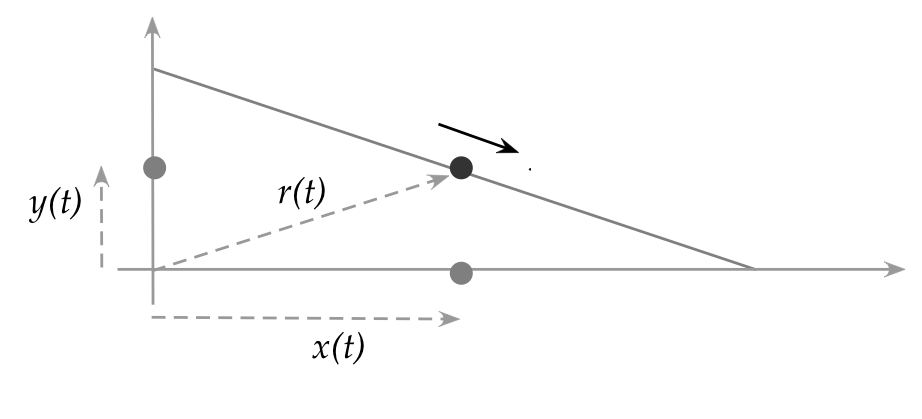

In the vectorized version (where we've simplified the object to a point object):

- The vector \(r(t)\) describes position.

- Because it's a vector, it has x,y components that are also changing with time: \(r(t) = (x(t), y(t))\)

- Suppose we observe the shadows on the x and y axes made by the object.

- The shadows move according to \(x(t)\) and and \(y(t)\).

- Note: \(x(t)\) and \(y(t)\) are vectors too!

- We've called them projections along the x and y axes.

- Since \(r(t), x(t), y(t)\) are vectors, we should switch to vector notation: \({\bf r}(t), {\bf x}(t), {\bf y}(t)\)

- Vector addition gives: \({\bf r}(t) = {\bf x}(t) + {\bf y}(t)\)

(As we would expect.) - Now, the differentiation operator is linear (remember?) and so $$ \frac{d{\bf r}(t)}{dt} \eql \frac{d{\bf x}(t)}{dt} + \frac{d{\bf y}(t)}{dt} $$

- That is, the object's motion can be completely reconstructed from the motions of its shadows on the axes.

- This holds for acceleration too.

- The power of linearity is that different rules can apply to each component.

- Thus the \({\bf x}(t)\) motion is not impacted by gravity, but \({\bf y}(t)\) is.

- When applying what matters to each component, one simply adds to get the actual location.