⇒ called object references in Java.

⇒ This is ObjX above.

class ObjX {

ObjX next; // Of the same type as ObjX.

}

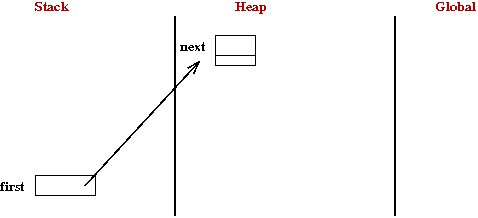

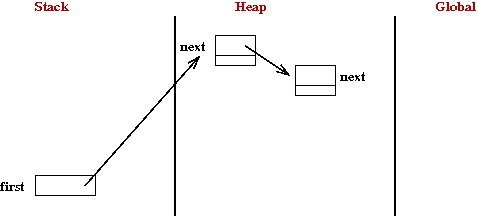

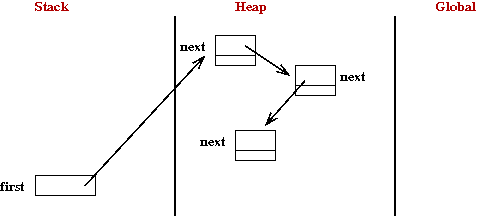

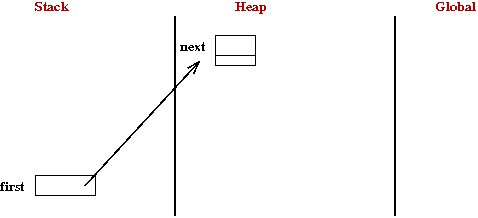

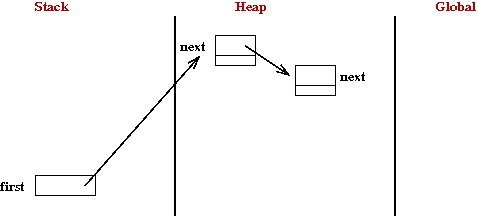

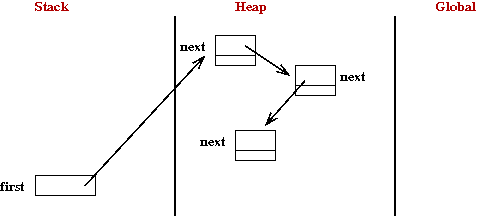

Consider the following simple example:

class ObjX {

ObjX next;

}

public class TestObjX {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

ObjX first = new ObjX (); // 1.

first.next = new ObjX (); // 2.

first.next.next = new ObjX (); // 3.

}

}

Note:

class ObjX {

ObjX next; // Of the same type as ObjX.

}

Let's start our study of linked lists in Java with a simple example.

Here is a simple linked list that stores integers:

(source file)

// This is a "node" in the list.

class ListItem {

public int data; // Integer data field.

ListItem next; // The familiar "next" pointer for

// a "singly-linked" list.

}

// We will temporarily write the code for creating and printing

// the list inside "main".

public class TestList {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// We need "front" and "rear" pointers.

ListItem front = null;

ListItem rear = null;

// Let's insert the numbers 1 to 10.

for (int i=1; i <= 10; i++) {

if (front == null) { // List empty.

front = new ListItem (); // Create listnode.

front.data = i; // Assign value.

rear = front;

rear.next = null;

}

else { // List non-empty.

rear.next = new ListItem (); // Create listnode at rear.

rear.next.data = i; // Assign value.

rear.next.next = null;

rear = rear.next; // Adjust rear pointer.

}

}

// Print the contents.

ListItem listPtr = front; // Start from front.

int i = 1;

while (listPtr != null) {

System.out.println ("item# " + i + ": " + listPtr.data);

i++;

listPtr = listPtr.next; // Walk to next item.

}

} // "main"

} // End of class "TestList"

Note:

class ListItem {

public int data; // Integer data field.

ListItem next; // The familiar "next" pointer.

// This is "singly-linked".

}

This is similar to a struct in C/C++.

ListItem next; // The familiar "next" pointer.

// This is "singly-linked".

if (front == null) { // List empty.

front = new ListItem (); // Create listnode.

front.data = i; // Assign value.

rear = front;

rear.next = null;

}

front.data = i; // Assign value.

This was possible because data has public visibility.

ListItem listPtr = front; // Start from front.

int i = 1;

while (listPtr != null) {

System.out.println ("item# " + i + ": " + listPtr.data);

i++;

listPtr = listPtr.next; // Walk to next item.

}

Let us create an improved linked list by placing the list manipulation functions in a separate class: (source file)

// List node.

class ListItem {

public int data = 0;

ListItem next = null;

}

// A separate list class.

class LinkedList {

// Instance variables.

ListItem front = null;

ListItem rear = null;

// Instance method to add a data item.

public void addData (int d)

{

if (front == null) {

front = new ListItem ();

front.data = d;

rear = front;

rear.next = null;

}

else {

rear.next = new ListItem ();

rear.next.data = d;

rear.next.next = null;

rear = rear.next;

}

}

// Instance method to print the list.

public void printList ()

{

ListItem listPtr = front;

int i = 1;

while (listPtr != null) {

System.out.println ("Item# " + i + ": " + listPtr.data);

i++;

listPtr = listPtr.next;

}

}

} // End of class "LinkedList"

class TestList2 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Create a new list object.

LinkedList L = new LinkedList ();

// Let's insert the numbers 1 to 10.

for (int i=1; i <= 10; i++) {

L.addData (i); // Use the addData() method.

}

// Print the contents.

L.printList();

// Create another list:

LinkedList L2 = new LinkedList ();

// and use it for whatever ...

}

} // End of class "TestList2"

Note:

class LinkedList {

// Instance variables.

ListItem front = null;

ListItem rear = null;

public void addData (int d)

{

// ...

}

public void printList ()

{

// ...

}

} // End of class "LinkedList"

Each linked list instance will have its own "front" and "rear" pointers, respectively.

Next, instead of leaving the

data field public, we will:The code: (source file)

class ListItem {

int data = 0;

ListItem next = null;

// Constructor.

public ListItem (int d)

{

data = d; next = null;

}

// Accessor.

public int getData ()

{

return data;

}

}

// Linked list class - also a dynamic class.

class LinkedList {

ListItem front = null;

ListItem rear = null;

int numItems = 0; // Current number of items.

// Could this class use a constructor?

// Instance method to add a data item.

public void addData (int d)

{

if (front == null) {

front = new ListItem (d); // Note use of constructor.

rear = front;

}

else {

rear.next = new ListItem (d); // Constructor use again.

rear = rear.next;

}

numItems++;

}

public void printList ()

{

ListItem listPtr = front;

System.out.println ("List: (" + numItems + " items)");

int i = 1;

while (listPtr != null) {

System.out.println ("Item# " + i + ": "

+ listPtr.getData());

// Note use of accessor.

i++;

listPtr = listPtr.next;

}

}

} // End of class "LinkedList"

Note:

Exercise 6.2: Add a method called memberOf (int d) to the above code so that you can test whether a particular integer is present in the list. Insert your code in the class LinkedList in the following template, which also tests your code. Draw a "memory picture" showing the contents of memory after the second iteration of the first for-loop in main().

We will now create a generic list that can be used with any object:

Here's how it works: (source file)

class ListItem {

Object data = null; // The universal Object.

ListItem next = null;

// Constructor.

public ListItem (Object obj)

{

data = obj; next = null;

}

// Accessor.

public Object getData ()

{

return data;

}

}

// Linked list class - also a dynamic class.

class LinkedList {

ListItem front = null;

ListItem rear = null;

int numItems = 0; // Current number of items.

// Instance method to add a data item.

public void addData (Object obj)

{

if (front == null) {

front = new ListItem (obj);

rear = front;

}

else {

rear.next = new ListItem (obj);

rear = rear.next;

}

numItems++;

}

public void printList ()

{

ListItem listPtr = front;

System.out.println ("List: (" + numItems + " items)");

int i = 1;

while (listPtr != null) {

System.out.println ("Item# " + i + ": "

+ listPtr.getData());

// Must implement toString()

i++;

listPtr = listPtr.next;

}

}

} // End of class "LinkedList"

// An object to use in the list:

class Person {

String name;

String ssn;

// Constructor.

public Person (String nameInit, String ssnInit)

{

name = nameInit; ssn = ssnInit;

}

// Override toString()

public String toString ()

{

return "Person: name=" + name + ", ssn=" + ssn;

}

} // End of class "Person"

// Test class.

class TestList4 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Create a new list object.

LinkedList L = new LinkedList ();

// Create a Person instance and add it to list.

Person p = new Person ("Terminator", "444-43-4343");

L.addData (p); // p is a subclass of Object and so

// p is automatically cast to Object

// We don't really need a Person variable:

L.addData (new Person ("Rambo", "555-54-5454"));

L.addData (new Person ("James Bond", "666-65-6565"));

L.addData (new Person ("Bruce Lee", "777-76-7676"));

// Print contents.

L.printList();

}

} // End of class "TestList4"

Note:

class ListItem {

Object data = null; // The universal Object.

ListItem next = null;

// Constructor.

public ListItem (Object obj)

{

data = obj; next = null;

}

// Accessor.

public Object getData ()

{

return data;

}

}

The constructor expects an Object instance as input and the accessor getData returns an Object reference (pointer).

class LinkedList {

// ... stuff

public void addData (Object obj)

{

}

// ... stuff

}

public void printList ()

{

//...

System.out.println ("Item# " + i + ": "

+ listPtr.getData());

// getData() returns an Object instance.

//...

}

class Person {

//...

public String toString ()

{

return "Person: name=" + name + ", ssn=" + ssn;

}

} // End of class "Person"

Person p = new Person ("Terminator", "444-43-4343");

L.addData (p);

To make the code very clear, we could add an explicit cast:

Person p = new Person ("Terminator", "444-43-4343");

L.addData ( (Object) p );

L.addData (new Person ("Rambo", "555-54-5454"));

Exercise 6.4:

In Exercise 6.2, you added a method called

memberOf (int d)

to the

LinkedList

class for membership testing. In this exercise, you will extend this idea

to generic lists by using the fact that

Object

defines a method called

equals(Object obj)

to allow two objects to test whether they are equal. Accordingly, you need

to override this method in class

Person

with the same signature:

public boolean equals (Object obj)

Insert your code in the class

Person

using the following template,

which also tests your code.

You will need to cast the

Object

parameter into a

Person

variable.

Often, it is convenient to be able to "walk" through a list and get its contents one-by-one.

A linked list that has this feature is sometimes called an enumeration object.

To create enumeration features, we will add the the following functions to the class LinkedList:

These functions can be used as follows (for example, with the class Person):

L.startEnumeration();

while (L.hasMoreElements()) {

Person p = (Person) L.getNextElement();

// ... Process p ...

System.out.println (p);

}

Here's the code: (source file)

class LinkedList {

// ... stuff ...

// The "cursor".

ListItem enumPtr = null;

// Start an enumeration.

public void startEnumeration ()

{

enumPtr = front;

}

public boolean hasMoreElements()

{

if (enumPtr == null)

return false;

else

return true;

}

public Object getNextElement()

{

Object obj = enumPtr.data;

enumPtr = enumPtr.next;

return obj;

}

} // End of class "LinkedList"

(The entire file is not shown).

Earlier, we created a generic linked list and were able to insert into it any object.

However, can we insert basic types like int's?

For example, we were able to insert Person instances:

L.addData (new Person ("Rambo", "555-54-5454"));

L.addData (new Person ("James Bond", "666-65-6565"));

L.addData (new Person ("Bruce Lee", "777-76-7676"));

One way to handle basic types is to convert each basic type into an equivalent object:

int i = 5;

Integer I = new Integer (i); // Integer object.

Thus, the following would work:

// Create a new list object.

GenericList L = new GenericList ();

// Let's insert 10 random numbers between 1 and 100

for (int i=1; i <= 10; i++) {

int k = (int) UniformRandom.uniform (1,100);

Integer K = new Integer (k); // Integer object.

L.addData (k);

}

// ... print etc ...

What is interesting is that the following will also work:

// Create a new list object.

GenericList L = new GenericList ();

// Let's insert 10 random numbers between 1 and 100

for (int i=1; i <= 10; i++) {

int k = (int) UniformRandom.uniform (1,100);

L.addData (k); // Automatic conversion to object equivalent (autoboxing)

}

// ... print etc ...

NOTE: this autoboxing feature was not available until JDK 1.5.

One final note on linked lists: to be really useful, the generic linked list ought to be in a separate file by itself, such as the file GenericList.java:

class ListItem {

// ...

}

// Linked list class.

public class GenericList {

// ...

}

Then, this class can be used elsewhere, say in a file called GenericListTest.java:

public class GenericListTest {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Create a new list object.

GenericList L = new GenericList ();

// Let's insert 10 random numbers between 1 and 100

for (int i=1; i <= 10; i++) {

int k = (int) UniformRandom.uniform (1L,100L);

L.addData (k);

}

// Enumerate items.

L.startEnumeration();

while (L.hasMoreElements()) {

int k = (int) L.getNextElement(); // Note use of autoboxing

System.out.println (k);

}

}

}

While the flexibility of inserting any object is useful,

it can also lead to problems, e.g.,

(source file)

class ListItem {

// ... as before ...

}

class LinkedList {

// ... as before ...

}

public class ListProblem {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

LinkedList L = new LinkedList ();

// Add stuff the list was originally designed for:

L.addData (new Integer(5));

L.addData (new Integer(6));

// Does this belong?

L.addData (new String("Blah-blah"));

// An application that fails:

L.startEnumeration ();

int sum = 0;

while ( L.hasMoreElements() ) {

Integer I = (Integer) L.getNextElement ();

sum = sum + I;

}

System.out.println ("sum=" + sum);

}

}

To address this problem, Java 1.5 added generics, a new language feature.

First, let's look at an example of using generics (from the Java library):

// Need this for java.util.ArrayList

import java.util.*;

public class ListProblem2 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// NOTE: this a data-structure in the Java library.

ArrayList<Integer> L = new ArrayList<Integer> ();

// Add stuff the list was originally designed for:

L.add (new Integer(5));

L.add (new Integer(6));

// This does not compile:

L.add (new String("Blah-blah"));

}

}

Next, let's see if we can write our own such generic list:

class ListItem<E> {

E data = null; // Note: the type is declared as E

ListItem next = null;

// Constructor: notice the type - same identifier as the class generic.

public ListItem (E obj)

{

data = obj; next = null;

}

// Accessor: notice the return type.

public E getData ()

{

return data;

}

}

class LinkedList<E> { // Again, a generic-type identifier

ListItem front = null;

ListItem rear = null;

int numItems = 0;

// Notice the type identifier as parameter:

public void addData (E obj)

{

if (front == null) {

front = new ListItem<E> (obj); // Example 1 of using the type

rear = front;

}

else {

rear.next = new ListItem<E> (obj);

rear = rear.next;

}

numItems++;

}

public void printList ()

{

// ...

}

}

class TestGeneric {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Notice how the actual type is provided:

LinkedList<Person> L = new LinkedList<Person> ();

// Create Person instances and add it to list.

L.addData (new Person ("Rogue", "1111-12-1212"));

L.addData (new Person ("Storm", "222-23-2323"));

L.addData (new Person ("Black Widow", "333-34-3434"));

L.addData (new Person ("Jean Grey", "888-89-8989"));

// Print contents.

L.printList();

// This won't compile:

L.addData (new String("blah-blah"));

}

}

Finally, let's look at the use of the for-each loop for such

data structures:

(source file)

// Need this for java.util.ArrayList.

import java.util.*;

public class TestGeneric2 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// This is a data-structure in the Java library:

ArrayList<Integer> L = new ArrayList<Integer> ();

// Add stuff the list was originally designed for:

L.add (new Integer(5));

L.add (new Integer(6));

L.add (new Integer(7));

L.add (new Integer(8));

// The for-each loop:

for (Integer I: L) {

System.out.println (I);

}

// An interesting variant that uses autoboxing:

for (int i: L) {

System.out.println (i);

}

}

}

Java provides several built-in data structures in its vast library. They are all in the package java.util. For example:

We will next look at some of these data structures.

We have seen how to exploit the all-super superclass Object to store any user-defined object in a list.

The same idea applies to the Stack class in java.util.

An example shows you how: (source file)

// Need to import from java.util.

import java.util.*;

// An object to use in the stack:

class Person {

String name;

String ssn;

// Constructor.

public Person (String nameInit, String ssnInit)

{

name = nameInit; ssn = ssnInit;

}

// Override toString()

public String toString ()

{

return "Person: name=" + name + ", ssn=" + ssn;

}

} // End of class "Person"

public class TestStack {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Create a new stack object.

Stack S = new Stack ();

// Create Person instances and add it to the Stack.

S.push (new Person ("Rogue", "1111-12-1212"));

S.push (new Person ("Storm", "222-23-2323"));

S.push (new Person ("Black Widow", "333-34-3434"));

S.push (new Person ("Jean Grey", "888-89-8989"));

// Pop the top of the stack. Note the cast needed.

Person p = (Person) S.pop();

System.out.println (p);

// Look at the top without popping. Note the cast needed.

p = (Person) S.peek();

System.out.println (p);

}

} // End of class "TestStack"

Note:

S.push (new Person ("Rogue", "1111-12-1212"));

Person p = (Person) S.pop();

public class TestStack2 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Create a new stack object, this time specifying the type.

Stack<Person> S = new Stack<Person> ();

// Create a Person instance and add it to the Stack.

S.push (new Person ("Rogue", "1111-12-1212"));

S.push (new Person ("Storm", "222-23-2323"));

S.push (new Person ("Black Widow", "333-34-3434"));

S.push (new Person ("Jean Grey", "888-89-8989"));

// Pop the top of the stack. NOTE: no cast needed.

Person p = S.pop();

System.out.println (p);

// Look at the top without popping. Again, no cast needed.

p = S.peek();

System.out.println (p);

}

}

Note:

Stack<Person> S = new Stack<Person> ();

Stack<Person> S = new Stack<Person> ();

can be shortened to

Stack<Person> S = new Stack<> ();

Here, the compiler derives the type from the left side of

the assignment.

The package java.util provides a simple hashtable that lets you:

The key itself can be an object.

Consider a simple example with strings:

import java.util.*;

public class TestHashtable {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

Hashtable h = new Hashtable ();

// Insert a string and a key.

h.put ("Ali", "Addled Ali");

h.put ("Bill", "Bewildered Bill");

h.put ("Chen", "Cantankerous Chen");

h.put ("Dave", "Discombobulated Dave");

// To retrieve, pass a key:

String d = (String) h.get ("Dave");

System.out.println (d); // Prints "Discombobulated Dave"

}

}

Note:

public Object put (Object key, Object obj)

Thus, in the call

h.put ("Dave", "Discombobulated Dave");

we pass the key (the string

"Dave")

first and then the object that needs to be stored (the string

"Discombobulated Dave").

public Object get (Object key)

and thus we pass the key ("Dave") as parameter

String d = (String) h.get ("Dave");

and get an Object

back. When using a non-typed data structure, this needs to be cast

back to a

String.

What happens if you insert two items that have the same key? For example:

public class TestHashtable2 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

Hashtable h = new Hashtable ();

// Insert a string and a key.

h.put ("Ali", "Addled Ali");

h.put ("Bill", "Bewildered Bill");

h.put ("Chen", "Cantankerous Chen");

h.put ("Dave", "Discombobulated Dave");

// Only one value can be stored for a particular key.

// Old value with same key is deleted.

h.put ("Dave", "Distracted Dave");

String d = (String) h.get ("Dave");

System.out.println (d); // Prints "Distracted Dave"

// You can get back the old value at the

// time of insertion.

String c = (String) h.put ("Bill", "Befuddled Bill");

System.out.println (c); // Prints "Bewildered Bill"

// The return value is null otherwise.

String e = (String) h.put ("Ed", "Egregious Ed");

System.out.println (e); // Prints "null".

}

}

Note:

Thus far, we have used Hashtable with String's.

A Hashtable can store any kind of object. For example: (source file)

// A class to store in the hashtable.

class Person {

// Instance data.

String name;

String nickname;

// Constructor.

public Person (String nameInit, String nickInit)

{

name = nameInit; nickname = nickInit;

}

// Accessor for name: we will use it as a key:

public String getName ()

{

return name;

}

// Overrides Object's toString()

public String toString()

{

return "Person: name=" + name + ", nickname=" + nickname;

}

} // End of class "Person"

public class TestHashtable3 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

Hashtable h = new Hashtable ();

Person p = new Person ("Franco", "Flummoxed Franco");

h.put (p.name, p);

p = new Person ("Gita", "Grumpy Gita");

h.put (p.name, p);

p = new Person ("Heinrich", "Huffy Heinrich");

h.put (p.name, p);

// When retrieving you get the whole object back.

p = (Person) h.get ("Heinrich");

System.out.println (p);

}

}

Note:

Instead of using String keys, any object can be used.

However, to make hashing work for a user-created object, several things need to be done:

To see what this means, consider the following example: (source file)

class NameAge {

String name;

int age;

// Constructor.

public NameAge (String nameInit, int ageInit)

{

name = nameInit; age = ageInit;

}

// Override toString()

public String toString ()

{

return "Name=" + name + ", Age=" + age;

}

// Overrides Object's hashCode()

public int hashCode()

{

// Shift name's hashCode left by 8 bits.

return 256*name.hashCode() + age;

}

// Overrides Object's equals()

public boolean equals (Object obj)

{

NameAge n = (NameAge) obj;

if ( (name.equals(n.name)) && (age==n.age) )

return true;

else

return false;

}

}

class Person {

// Instance data.

NameAge na;

String nickname;

// Constructor.

public Person (String nameInit, int ageInit, String nickInit)

{

na = new NameAge (nameInit, ageInit);

nickname = nickInit;

}

// Overrides Object's toString()

public String toString()

{

// Observe use of NameAge's toString() here:

return "Person: " + na + ", nickname=" + nickname;

}

// Accessor for NameAge so that it can be used as key.

public NameAge getNameAge ()

{

return na;

}

}

public class TestHashtable4 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

Hashtable h = new Hashtable ();

Person p = new Person ("Franco", 25, "Flummoxed Franco");

h.put (p.getNameAge(), p);

p = new Person ("Gita", 18, "Grumpy Gita");

h.put (p.getNameAge(), p);

p = new Person ("Heinrich", 43, "Huffy Heinrich");

h.put (p.getNameAge(), p);

// When retrieving you get the whole object back.

NameAge query = new NameAge ("Heinrich", 43);

p = (Person) h.get (query);

System.out.println (p);

}

}

Note:

public int hashCode()

{

// Shift name's hashCode left by 8 bits.

return 256*name.hashCode() + age;

}

NameAge query = new NameAge ("Heinrich", 43);

p = (Person) h.get (query);

Suppose you have a "properties" text file that looks like:

Circle1.center.x=100 Circle1.center.y=250 Circle1.radius=30 Circle2.center.x=60 Circle2.center.y=90 Circle2.radius=10

Java defines a Properties class that reads in such a file and extracts individual property names and values.

The

Properties

class is similar to a

Hashtable

except that it works only with

Strings

and with files in the above form.

(In fact, Properties

is derived from

Hashtable).

First, consider creating a properties file: (source file)

public class TestProperties {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Create a new Properties object.

Properties p = new Properties();

// Insert some properties.

p.put ("Circle1.center.x", "100");

p.put ("Circle1.center.y", "250");

p.put ("Circle1.radius", "30");

// Note: both the property name and

// the value are String's.

p.put ("Circle2.center.x", "60");

p.put ("Circle2.center.y", "90");

p.put ("Circle2.radius", "10");

p.put ("Square1.topleft.x", "300");

p.put ("Square1.topleft.y", "400");

p.put ("Square1.side", "40");

// Print all the properties to the screen.

p.save (System.out, "Geometric objects");

// Write the properties to text file called "geodata"

try {

// File-related IO requires try-catch.

FileOutputStream f = new FileOutputStream ("geodata");

p.save (f, "Geometric objects");

}

catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println ("Cannot open file");

System.exit(0);

}

}// "main"

} // End of class "TestProperties"

Note:

p.put ("Circle1.center.x", "100");

p.put ("Circle1.center.y", "250");

p.put ("Circle1.radius", "30");

Here, the property name acts like a key.

public void save (OutputStream out, String header)

which means any output stream can be passed to it.

p.save (System.out, "Geometric objects");

This results in the list of properties being written

to the screen.

try {

FileOutputStream f = new FileOutputStream ("geodata");

p.save (f, "Geometric objects");

}

catch (IOException e) {

// ...

}

This results in the list of properties being written

to file

"geodata".

(Note: the constructor of

FileOutputStream

throws an exception, which must be caught).

#Geometric objects #Wed Sep 23 15:16:04 EDT 1998 Circle1.center.y=250 Circle1.center.x=100 Square1.topleft.y=400 Square1.topleft.x=300 Circle1.radius=30 Circle2.radius=10 Circle2.center.y=90 Circle2.center.x=60 Square1.side=40

Here is how properties can be read from a file like "geodata": (source file)

public class TestProperties2 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Create an instance of a Properties class.

Properties p = new Properties();

// Read from a text file with properties ("geodata").

try {

FileInputStream f = new FileInputStream ("geodata");

// Use the "load" method in a Properties object.

p.load (f);

}

catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println ("Cannot open file");

System.exit(0);

}

// Retrieve property values.

String cx = p.getProperty ("Circle1.center.x");

String cy = p.getProperty ("Circle1.center.y");

String r = p.getProperty ("Circle1.radius");

System.out.println ("Circle1: cx=" + cx + ", cy=" + cy

+ ", r=" + r);

}

}

Suppose we have read a properties file using a Properties class and suppose we want to scan the properties one by one.

Java defines a generic Enumeration class that lets you scan through components one by one.

Consider the following example with a Properties class: (source file)

public class TestProperties3 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

Properties p = new Properties();

// Read properties from the file "geodata".

try {

FileInputStream f = new FileInputStream ("geodata");

p.load (f);

}

catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println ("Cannot open file");

System.exit(0);

}

// The entire list of property NAMES can be enumerated.

System.out.println ("Property Names: ");

Enumeration e = p.propertyNames();

while (e.hasMoreElements()) {

System.out.println (e.nextElement());

}

} // "main"

}

Note:

public Enumeration propertyNames()

Enumeration e = p.propertyNames();

while (e.hasMoreElements()) {

String propName = (String) e.nextElement();

// Do something with propName.

}

public abstract interface Enumeration {

public abstract boolean hasMoreElements();

public abstract Object nextElement();

}

We will understand what this means when we study abstract classes and interface's.

The library class System in java.lang defines a method called:

public Properties getProperties()

The idea is, you can call this method to learn something about the current system.

For example: (source file)

public class SystemProperties {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// The System class has a static function that

// returns a Properties object:

Properties p = System.getProperties();

// The entire list of properties can be enumerated.

Enumeration e = p.propertyNames();

while (e.hasMoreElements()) {

String propName = (String) e.nextElement();

String propVal = p.getProperty (propName);

System.out.println (propName + "=" + propVal);

}

}

}

This example prints out various system properties

such as the

PATH, CLASSPATH,

version of compiler, location of the system executables etc.

Curious? Try it out!