Module 10: Supplemental Material

Expression trees

What is an expression tree?

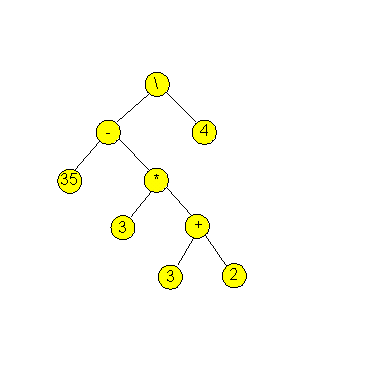

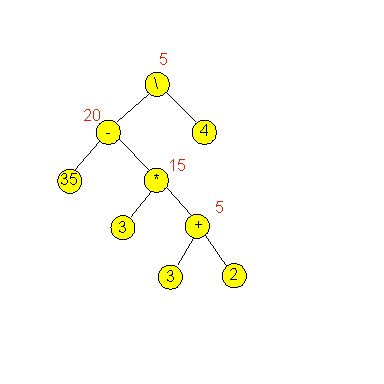

- Consider arithmetic expressions like (35 - 3*(3+2)) / 4:

- For our discussion we'll consider the four arithmetic operators:

+, -, *, /.

- We'll study integer arithmetic

⇒

Here, the /-operator is integer-division (e.g., 2/4 = 0)

- Each operator is a binary operator

⇒

Takes two numbers and returns the result (a number)

- There is a natural precedence among operators:

\, *, +, -.

- We'll use parentheses to force a different order, if needed:

- Thus 35 - 3*3+2/4 = 26 (using integer arithmetic)

- Whereas (35 - 3*(3+2)) / 4 = 5

- Now let's examine a computational procedure for expressions:

- At each step, we apply one of the operators.

- The rules of precedence and parentheses tell us the order.

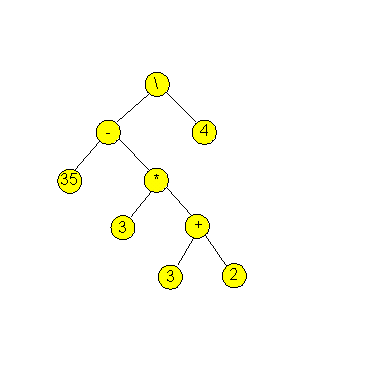

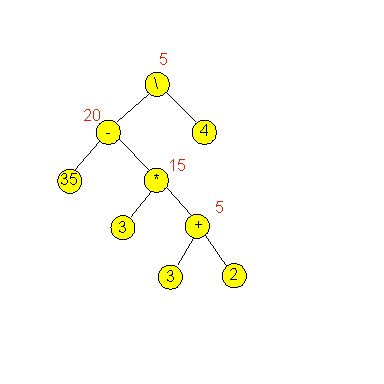

- The computational procedure can be written as an expression tree:

- In an expression tree:

- The leaves are numbers (the operands).

⇒

The value of a leaf is the number.

- The non-leaf nodes are operators.

⇒

The value of a non-leaf node is the result of the operator applied to the values of the left and right child.

- The root node corresponds to the final value of the expression.

Exercise 1:

Draw an expression tree for the expression 10/4 + 2*(5+1).

Compute the values at each non-leaf node.

We will now look at a variety of issues related to expression trees:

- How to build a tree given an expression.

- How to evaluate an expression tree, once it's built.

- How to convert expressions to postfix form and why that's important.

Let's start with building the tree:

- The computational procedure for extracting the sub-parts (numbers, and operators) of an expression like (35-3*(3+2))/4 is called parsing.

- To simplify the code, we'll make extensive use of parentheses:

- Every number will be surrounded by parentheses.

- Every operator with its operand will be enclosed in parentheses.

- Of course, parsing can be done with theses restrictions

⇒

But the code is more complicated

- Thus, the expression (35-3*(3+2))/4 becomes

(((35)-((3)*((3)+(2))))/(4))

Exercise 2:

Convert the expression 10/4 + 2*(5+1) into the

form above, with complete parentheses.

We will build the tree as we go along in the parsing:

- We'll use this class as the template for each tree node:

class ExprTreeNode {

ExprTreeNode left, right; // The usual pointers.

boolean isLeaf; // Is this a leaf?

int value; // If so, we'll store the number here.

char op; // If not, we need to know which operator.

}

- The general idea in our parsing algorithm is:

Algorithm: parse (e)

Input: expression string e

Output: root of expression subtree for e

1. node = make new tree node.

// Bottom-out: it's a number

2. if e is a number

3. node.value = number extracted from string

4. return node

5. endif

// Recurse

6. node.op = extract operator from e

7. node.left = parse (substring of e to the left of op)

8. node.right = parse (substring of e to the right of op)

9. return node

- We'll need to write code to look inside a string and identify the left and right substrings (on either side of the operator).

Here's the program:

// We need this for the Stack class.

import java.util.*;

class ExprTreeNode {

ExprTreeNode left, right; // The usual pointers.

boolean isLeaf; // Is this a leaf?

int value; // If so, we'll store the number here.

char op; // If not, we need to know which operator.

}

class ExpressionTree {

ExprTreeNode root;

public void parseExpression (String expr)

{

root = parse (expr);

}

// This is the recursive method that does the parsing.

ExprTreeNode parse (String expr)

{

ExprTreeNode node = new ExprTreeNode ();

// Note: expr.charAt(0) is a left paren.

// First, find the matching right paren.

int m = findMatchingRightParen (expr, 1);

String leftExpr = expr.substring (1, m+1);

// Bottom-out condition:

if (m == expr.length()-1) {

// It's at the other end ⇒ this is a leaf.

String operandStr = expr.substring (1, expr.length()-1);

node.isLeaf = true;

node.value = getValue (operandStr);

return node;

}

// Otherwise, there's a second operand and an operator.

// Find the left paren to match the rightmost right paren.

int n = findMatchingLeftParen (expr, expr.length()-2);

String rightExpr = expr.substring (n, expr.length()-1);

// Recursively parse the left and right substrings.

node.left = parse (leftExpr);

node.right = parse (rightExpr);

node.op = expr.charAt (m+1);

return node;

}

int findMatchingRightParen (String s, int leftPos)

{

// Given the position of a left-paren in String s,

// find the matching right paren.

// Recognize the code?

Stack<Character> stack = new Stack<Character>();

stack.push (s.charAt(leftPos));

for (int i=leftPos+1; i < s.length(); i++) {

char ch = s.charAt (i);

if (ch == '(') {

stack.push (ch);

}

else if (ch == ')') {

stack.pop ();

if ( stack.isEmpty() ) {

// This is the one.

return i;

}

}

}

// If we reach here, there's an error.

System.out.println ("ERROR: findRight: s=" + s + " left=" + leftPos);

return -1;

}

int findMatchingLeftParen (String s, int rightPos)

{

// ... similar ...

}

int getValue (String s)

{

try {

int k = Integer.parseInt (s);

return k;

}

catch (NumberFormatException e) {

return -1;

}

}

} // end-ExpressionTree

Exercise 3:

Show how the recursion works for the expression

(((35)-((3)*((3)+(2))))/(4)). That is, draw

the sequence of "stack snapshots" showing recursive

calls to the parse() method.

Next, let's write code for computing the value of the expression

after it's been parsed:

- This too is written recursively:

Algorithm: computeValue (node)

Input: a root of a subtree

Output: the value of the subtree

1. if node is a leaf

2. return the node's value // The number that the node represents

3. endif

4. leftValue = computeValue (node.left)

5. rightValue = computeValue (node.right)

6. result = apply node.op to leftValue and rightValue

7. return result

- In our program:

class ExpressionTree {

// ...

public int computeValue ()

{

return compute (root);

}

int compute (ExprTreeNode node)

{

if (node.isLeaf) {

return node.value;

}

// Otherwise do left and right, and add.

int leftValue = compute (node.left);

int rightValue = compute (node.right);

if (node.op == '+') {

return leftValue + rightValue;

}

else if (node.op == '-') {

return leftValue - rightValue;

}

else if (node.op == '*') {

return leftValue * rightValue;

}

else {

return leftValue / rightValue;

}

}

// ...

}

- Thus, we can now parse and compute expressions:

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// A test expression:

String s = "(((35)-((3)*((3)+(2))))/(4))";

// Create a parser instance.

ExpressionTree expTree = new ExpressionTree ();

// Parse the expression (which creates the tree).

expTree.parseExpression (s);

// Compute the value and print.

int v = expTree.computeValue ();

System.out.println (s + " = " + v);

}

Why did we do all this?

- Parsing is an integral part of compilation

⇒

We only explored a small part of parsing (expressions)

- Parsing and trees are intimately related

⇒

The result of parsing a program is a tree

- The output of a compiler is executable code of some kind

⇒

Parsing is a pre-requisite step to generating executable code.

Postfix expressions

What are they?

- For simplicity, we'll consider only the four integer arithmetic

operators: +, -, *, /.

- In a postfix expression:

- The operands are listed before the operators.

- Operators just after the two operands.

- Thus, the expression 3 + 4 in postfix becomes: 3 4 +.

- Example: the expression 5*(3+4) becomes: 5 3 4 + *.

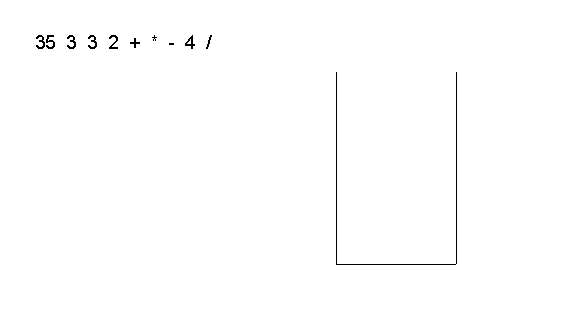

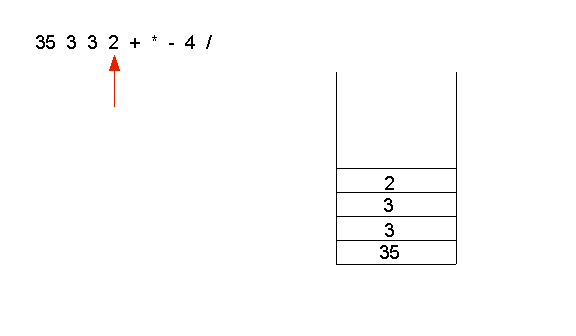

- Example: the expression (35 - 3*(3+2)) / 4 becomes:

35 3 3 2 + * - 4 /

Exercise 4:

Convert the expression 10/4 + 2*(5+1) into postfix form.

Postfix expressions are evaluated using a stack:

- A postfix expression is read from left to right.

- Every operand is pushed on the stack.

- When an operator is encountered, it is applied to the top two operands on the stack.

- The result of the operation is pushed back on the stack

⇒

The stack only contains numbers

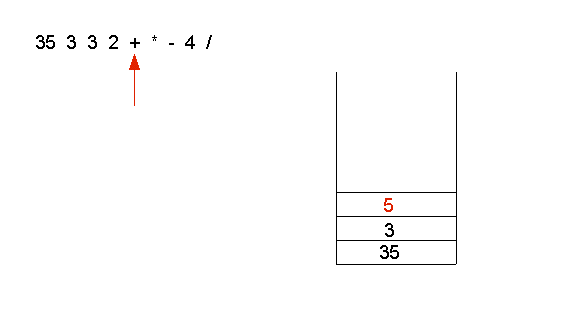

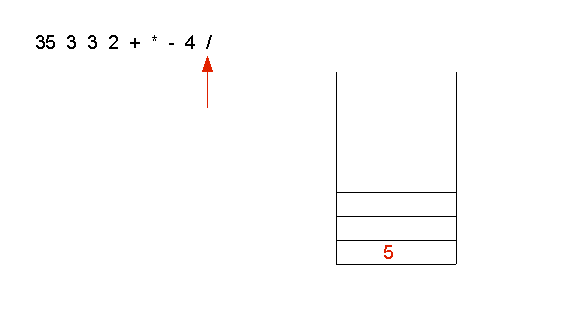

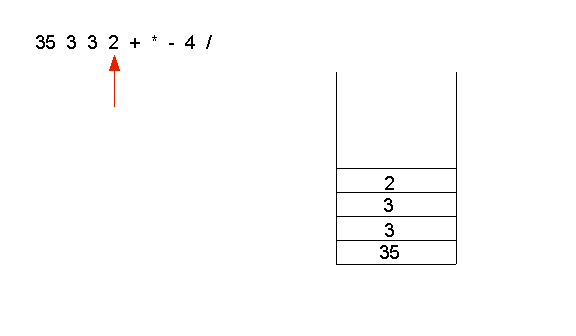

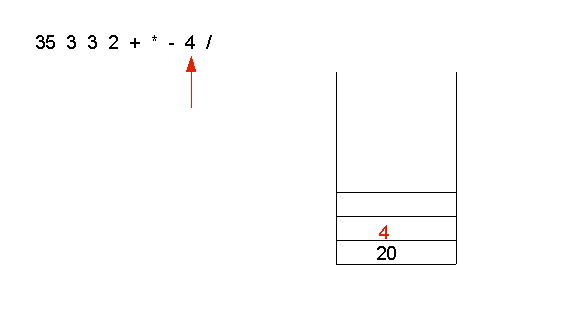

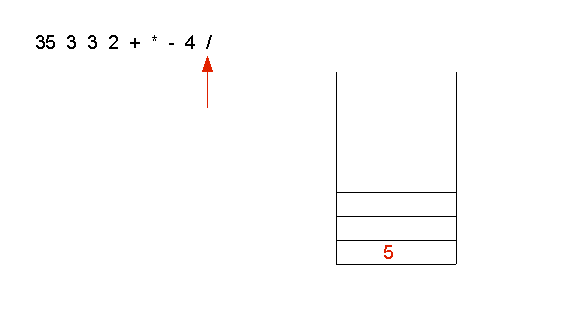

Example: let's evaluate the expression 35 3 3 2 + * - 4 /

- Initially the stack is empty:

- The first four operands get pushed on the stack:

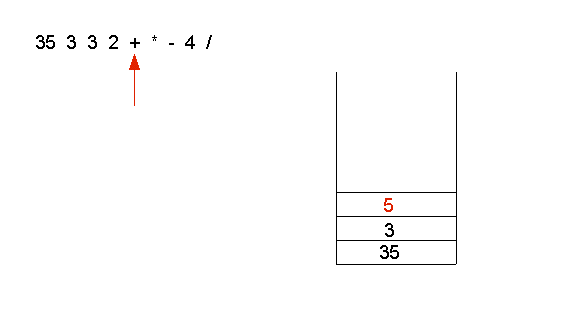

- Then, the operator + is applied to the top two operands (3 and 2)

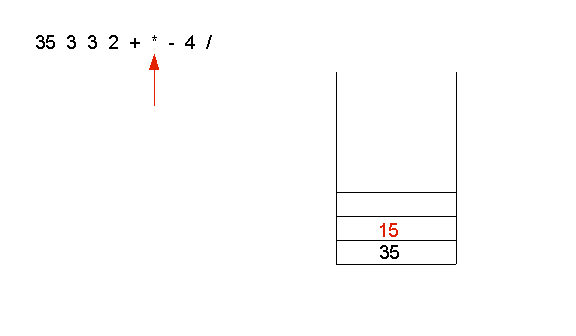

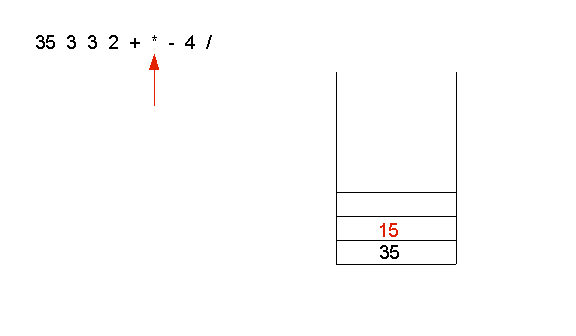

- Next, the operator * is applied to 5 and 3:

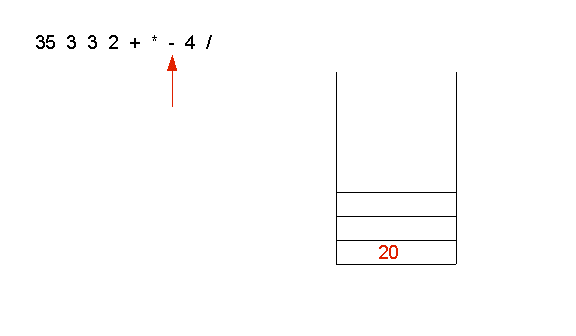

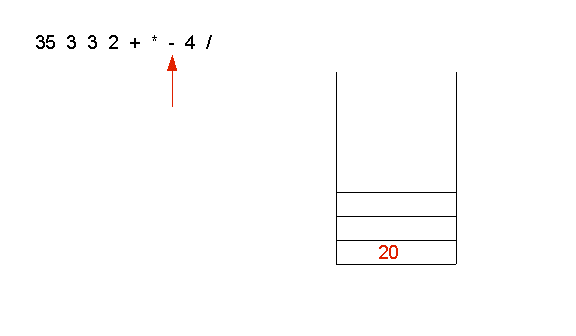

- The operator - is applied to 15 and 35

(as 35-15)

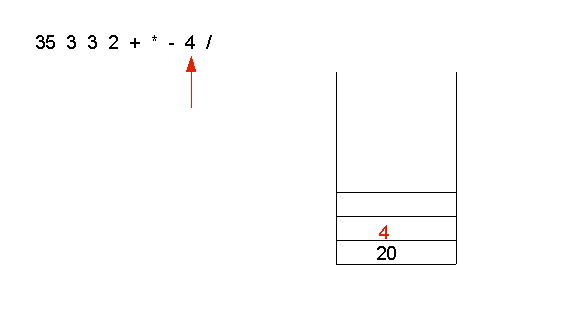

- The operand 4 is pushed on the stack:

- Finally, the operator / is applied to 4 and 20:

Exercise 5:

Convert the expression 10/4 + 2*(5+1) into postfix form

and show the steps in evaluating the expression using a stack.

Draw the stack at each step.

Why is this useful?

- First, let's list the stack operations in the order

they were used in the previous example:

push 35

push 3

push 3

push 2

add

mult

sub

push 4

divide

- We can think of these as instructions for operating

a stack-based calculator.

Exercise 6:

Convert the expression 10/4 + 2*(5+1) into postfix form

and write down the push/arithmetic "instructions" corresponding

to this expression.

- There are computer architectures whose instruction sets

are similar

⇒

They use a stack-based calculator as part of the CPU.

- Similarly there are virtual machines (e.g., Java's VM)

that use a stack-based calculator

- The list of "instructions" is in fact a form of

executable code for these kinds of machines.

⇒

Thus, we've given a sense of how arithmetic expressions are compiled into executable code.

Now let's write code to create postfix from an expression tree

and then to evaluate it using a stack:

- The conversion to postfix is easy: simply traverse the tree in postfix order!

- For example, we can add such a method to our

class ExpressionParser:

class ExpressionTree {

ExprTreeNode root;

public String convertToPostfix ()

{

String str = postOrder (root);

return str;

}

String postOrder (ExprTreeNode node)

{

String result = "";

if (node.left != null) {

result += postOrder (node.left);

}

if (node.right != null) {

result += " " + postOrder (node.right);

}

if (node.isLeaf) {

result += " " + node.value;

}

else {

result += " " + node.op;

}

return result;

}

} //end-ExpressionParser

- Let's write code to evaluate a postfix-expression string

using a stack:

class PostfixEvaluator {

public int compute (String postfixExpr)

{

// Create a stack: all our operands are integers.

Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<Integer>();

// Use the Scanner class to help us extract numbers or operators:

Scanner scanner = new Scanner (postfixExpr);

while (scanner.hasNext()) {

if (scanner.hasNextInt()) {

// It's an operand ⇒ push it on the stack.

int N = scanner.nextInt();

stack.push (N);

}

else {

// It's an operator ⇒ apply the operator to the top two operands

String opStr = scanner.next();

int b = stack.pop(); // Note: b is popped first.

int a = stack.pop();

if (opStr.equals("+")) {

stack.push (a+b);

}

else if (opStr.equals("-")) {

stack.push (a-b);

}

else if (opStr.equals("*")) {

stack.push (a*b);

}

else if (opStr.equals("/")) {

stack.push (a/b);

}

}

} // end-while

// Result is on top.

return stack.pop();

}

} //end-PostfixEvaluator

Enumerating the elements of a data structure

Let's revisit our binary tree map:

- Recall: a map stores key-value pairs.

- Suppose we create a map instance and put some key-value pairs as follows:

class TribeInfo {

// ... same as before ...

}

public class BinaryTreeMapExample3 {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Create an instance.

BinaryTreeMap3 tree = new BinaryTreeMap3 ();

// Put some key-value pairs inside.

TribeInfo info = new TribeInfo ("Ewok", 3, "Endor");

tree.add ( new KeyValuePair (info.name, info) );

// ... add the remaining data ...

}

}

- Now suppose we wish to work with the entire collection,

say, as an array:

// Get all the key-value pairs:

KeyValuePair[] tribes = tree.getAllKeyValuePairs ();

// Print.

for (int i=0; i < tribes.length; i++) {

System.out.println (tribes[i]);

}

- Then, we need to have the binary-tree return all its elements

as an array.

- This feature is usually provided by implementations of data structures

⇒

It enables users of the data structure to work with the entire collection.

How do we implement the method getAllKeyValuePairs()?

- We will build an array and use an in-order traversal to place

elements in the array.

- Here's the code:

public class BinaryTreeMap3 {

TreeNode root = null;

int numItems = 0;

KeyValuePair[] allPairs; // We will place the elements in this array.

int currentIndex = 0;

// ... other methods like add(), contains() ... etc

public KeyValuePair[] getAllKeyValuePairs ()

{

if (root == null) {

return null;

}

allPairs = new KeyValuePair [numItems];

inOrderTraversal (root);

return allPairs;

}

void inOrderTraversal (TreeNode node)

{

// Visit left subtree first.

if (node.left != null) {

inOrderTraversal (node.left);

}

// Then current node.

allPairs[currentIndex] = node.kvp;

currentIndex ++;

// Now right subtree.

if (node.right != null) {

inOrderTraversal (node.right);

}

}

} //end-BinaryTreeMap3

Exercise 7:

Download BinaryTreeMap3.java

and BinaryTreeMapExample3.java,

compile and execute. You will notice that the output is sorted,

whereas the input (the order in which the strings were added)

was not. How/where did the sorting occur?

Using special purpose iterator classes:

- Sometimes it is more convenient to use iterator classes.

- For example:

import java.util.*;

public class StringExample {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

// Make a tree (of strings) and add stuff to it.

TreeSet<String> tribes = new TreeSet<String>();

tribes.add ("Ewok");

tribes.add ("Aqualish");

tribes.add ("Gungan");

tribes.add ("Amanin");

tribes.add ("Jawa");

tribes.add ("Hutt");

tribes.add ("Cerean");

// Get the data structure to return an object that does the iteration.

Iterator iter = tribes.iterator ();

// Now use the iterator object to perform iteration.

while (iter.hasNext()) {

String name = (String) iter.next (); // Note: a cast is required.

System.out.println (name);

}

}

}

Exercise 8:

Why is a cast required above?

It turns out that we can use an iterator specialized

to strings:

Iterator<String> iter = tribes.iterator ();

while (iter.hasNext()) {

String name = iter.next (); // No cast needed.

System.out.println (name);

}

Note:

- How do we build this feature into our own data structures?

⇒

This is a somewhat complicated topic

⇒

See Modules 6-7 of the

advanced Java material

- It is even more complicated to write our own iterable versions of

data structures that can be specialized to particular types (e.g., strings or integers).

⇒

This involves the murky details of generic types in Java.

An application: word counts

Let us develop a simple application of map's: count the number

of occurences of words in a body of text:

- For example, consider this body of text:

The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog, after which

the dog jumped on the fox and bit the fox,

after which their friendship ended rather abruptly.

For this example, we want the output to read something like:

4 the // 4 occurences of "the" in the text

3 fox // 3 occurences of "fox" in the text

2 jumped // ... etc

2 dog

2 after

2 which

1 quick

1 brown

...

- Our algorithm for this application is quite simple:

Algorithm: wordCount

Output: word counts

1. while more words

2. w = getNextWord()

3. if w is not in dictionary

4. add w to dictionary

5. set w's count to 1

6. else

7. increment w's count

8. endif

9. endwhile

10. Print counts for each word

- We will compare a tree data structure with a list.

Here's the program:

import java.util.*;

public class WordCount {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

countWordsInFileUsingTree ("testfile");

countWordsInFileUsingList ("testfile");

}

static void countWordsInFileUsingTree (String fileName)

{

// Create an instance of the data structure.

BinaryTreeMap3 tree = new BinaryTreeMap3 ();

// Read a text file and extract the words into an array.

String[] words = WordTool.readWords (fileName);

System.out.println ("Read in " + words.length + " words");

// Put words into data structure. If a word repeats, increment its count.

for (int i=0; i// Increment count.

KeyValuePair kvp = tree.getKeyValuePair (words[i]);

Integer count = (Integer) kvp.value;

kvp.value = new Integer (count+1);

}

}

// Note use of array:

KeyValuePair[] uniqueWords = tree.getAllKeyValuePairs ();

System.out.println ("Found " + uniqueWords.length + " unique words");

// Sort the words by count.

Arrays.sort (uniqueWords, new KeyValueComparator());

for (int i=0; i < uniqueWords.length; i++) {

System.out.println (uniqueWords[i].value + " " + uniqueWords[i].key);

}

}

static void countWordsInFileUsingList (String fileName)

{

// Our data structure is now a linked list.

OurLinkedListMap list = new OurLinkedListMap ();

// ... everything else is the same ...

}

} //end-WordCount

Note:

- We have hidden text-parsing and word-extraction in WordTool.

- The relevant data structure methods we've used are:

- add()

- contains()

- getAllKeyValuePairs() (to get all the key-value pairs as an array)

- Notice why we get all the key-value pairs as an array

⇒

So that we can sort by value

Exercise 9:

Download BinaryTreeMap3.java,

OurLinkedListMap.java,

WordCount.java and

testfile. Compile and execute

WordCount to make sure it works.

Then, perform word counts for

this classic book

and

this one.

You can comment out the linked-list version (since it

does the same thing and does it slower).

Find another free book on-line and apply WordCount to the book.

Exercise 10:

Compare the performance between a tree, a hashtable and

a linked list for the two large texts above.

You will need to add code to use a hashtable for

counting. Use OurHashMap.java

as the hashtable.

Finally, let us explain how we used Java's sorting algorithm above:

- First, let's examine the usage:

KeyValuePair[] uniqueWords = tree.getAllKeyValuePairs ();

// Sort the words by count.

Arrays.sort (uniqueWords, new KeyValueComparator());

- Thus, we start with an unsorted array of objects (uniqueWords)

- In this case, each object is a KeyValuePair.

- We call the method sort() in the Arrays class in the library.

- We pass on an instance of KeyValueComparator to the sort algorithm.

- Obviously, Java's sort algorithm does not know how to sort

arbitrary objects that we've created ourselves (such as KeyValuePair)

⇒

Recall: we wrote KeyValuePair ourselves.

- Every sort algorithm needs to be able to compare any two elements

⇒

Thus, a sort algorithm needs to be able to compare two KeyValuePair instances.

- The idea is: we will write a method to do such a comparison

and pass that to Java's sort algorithm.

- But how do we pass a method?

- We can't. Instead, we pass a class with our method.

- In our example, that class is KeyValueComparator, a class that we will write.

- How does Java's sort method know which method to call inside KeyValueCompartor?

⇒

Since Java's sort method is already written and

compiled, it already calls some method

⇒

It is this method that we need to override.

Let's look at some of the details:

- The signature of Java's sort method (the one that we want to

use) is:

public void sort (Object[] inputArray, Comparator comp)

(Note: we have simplified it slightly to remove references to

generic types).

- If we look for Comparator in the library, we see

that it is an interface:

public interface Comparator {

public int compare (Object o1, Object o2);

public boolean equals (Object obj);

}

(Again, we've simplified this by removing generic types).

- Thus, Java's sort algorithm will call the compare

method of whatever class is passed in as Comparator in

order to compare the objects in inputArray.

- What we are going to do is pass an array of

KeyValuePair's as the first argument.

- For the second argument, we will create an instance of:

class KeyValueComparator implements Comparator {

// We decide how to compare two key-value pairs. Java's sort

// algorithm will repeatedly call this as it compares elements.

public int compare (KeyValuePair kvp1, KeyValuePair kvp2)

{

// Note: the .value variable is of type Object. That's why we need the cast.

Integer count1 = (Integer) kvp1.value;

Integer count2 = (Integer) kvp2.value;

if (count1 > count2) {

return -1;

}

else if (count1 < count2) {

return 1;

}

else {

return 0;

}

}

// We're required to implement this as part of implementing

// the interface.

public boolean equals (Object obj)

{

return false;

}

} //end-KeyValueComparator

Note:

- Notice that our KeyValueComparator class

implements the interface Comparator

- Here, we have provided an implementation of

compare() (and equals(), which is required by

the interface but not used by the sort algorithm).

- We write whatever code we like inside compare().

- Of course, we really do want to properly compare two

KeyValuePair objects.

⇒

Which is why we extract the integer's from the objects and

compare them.

- When Java's sort gets this object, it calls

compare() whenever it needs to (which is very often).

- Finally, we note that Comparator is really intended

to be written for specific types, which we removed to simplify

the description.

⇒

In our code, we specified the type as KeyValuePair:

class KeyValueComparator implements Comparator<KeyValuePair> {

public int compare (KeyValuePair kvp1, KeyValuePair kvp2)

{

// ...

}

}

Exercise 11:

Add a counter to KeyValueComparator above to count how often

the compare() method is called. What is the relation between

this count and the size of the array being sorted?

Exercise 12:

Examine the logic in compare(). What would happen if

we switch the first two return statements to read:

if (count1 > count2) {

return 1;

}

else if (count1 < count2) {

return -1;

}

else {

return 0;

}

Try it out and see what happens. Then explain what happened.

© 2006, Rahul Simha (revised 2017)