The goal of this module is to review some key ideas

in programming:

- Variables, both basic and arrays.

- Loops.

- Conditionals.

- Methods.

For this purpose, we will use some contrived but

simplified examples to drive home important points.

Most of our focus will be on methods.

Variables

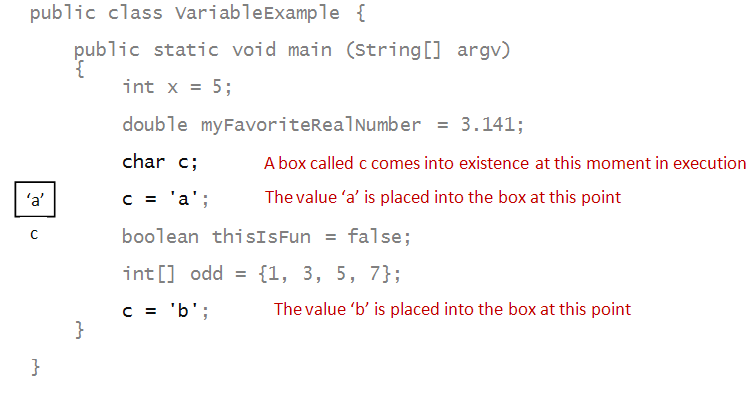

Consider this example:

public class VariableExample {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

int x = 5;

double myFavoriteRealNumber = 3.141;

char c;

c = 'a';

boolean thisIsFun = false;

int[] odd = {1, 3, 5, 7};

x = odd[0] + odd[3];

c = 'b';

}

}

Variables have three aspects to them:

- A name, like x or thisIsFun above.

=> Variable names don't change in a program, they are fixed at compile time.

- A current value.

=> At any moment during execution, a variable has a value.

This value can change (often does) during execution.

- A scope. More about this later.

- A type, like int or boolean.

About variables:

- Think of a basic variable as a labelled box that can

hold one value at any moment.

- The four basic variable types we have

covered:

- int - these variables take values like -3, 14, 2556.

- double - these variables take values like -3.141, 14, 2556.339.

- char - these variables take values like 'a', ' ', '$'.

- boolean - these variables take values true or false only.

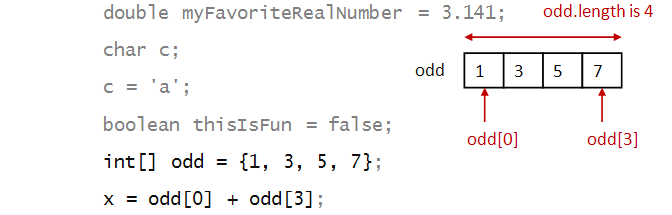

- Think of an array variable as referring to a sequentially

ordered collection of boxes:

- An array variable, like odd, represents

the whole array.

- We use the square brackets, as in odd[0],

to access a particular element of the array.

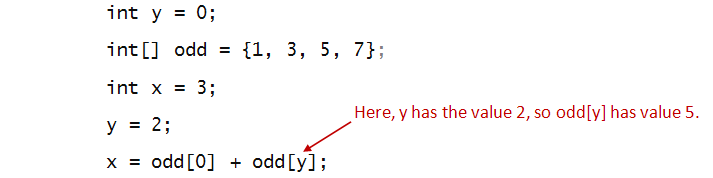

- One can use either a fixed constant, like 0 or

an int variable for such an access:

Visualization of execution

First, let's review mental execution and develop

some useful visualizations:

- Consider this program

public class SillyProgram {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

int x = 1;

int y;

x = x + 1;

y = x*x;

System.out.println (y);

}

}

- When you see such a program, you should say ...

- Execution starts with the first line in main.

- Here, an int variable x is declared and assigned

the value 1.

- Then, the int variable y is declared, but

not assigned a value ... etc.

- Thus, execution proceeds sequentially in order

of the appearance of statements.

So far, so good. Next, let's look at:

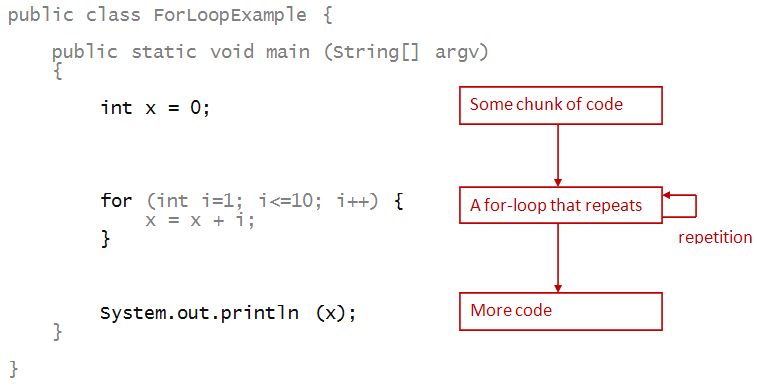

public class ForLoopExample {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

int x = 0;

for (int i=1; i<=10; i++) {

x = x + i;

}

System.out.println (x);

}

}

There are four levels at which to "read" or understand

a for-loop:

- First, at the highest level, a for-loop is merely

a block of code that repeats a number of times:

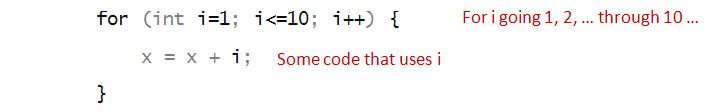

- At the next level, you should say to yourself,

"for i starting at 1 up through 10 ...(something)"

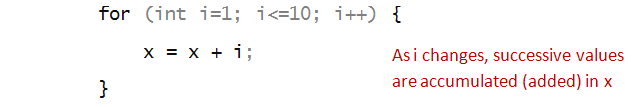

- At the third level, you can try and understand

what the loop is trying to do:

- Finally, at the most detailed level, you trace through

the loop, watching how every affected variable changes its value.

=> Here, only x and i change.

i x

0. Before loop starts 0

1. End of 1st iteration 1 1

2. 2nd 2 3

3. 3rd 3 6

4. 4th 4 10

5. 5th 5 15

6. 6th 6 21

7. 7th 7 28

8. 8th 8 36

9. 9th 9 45

10. last iteration 10 55

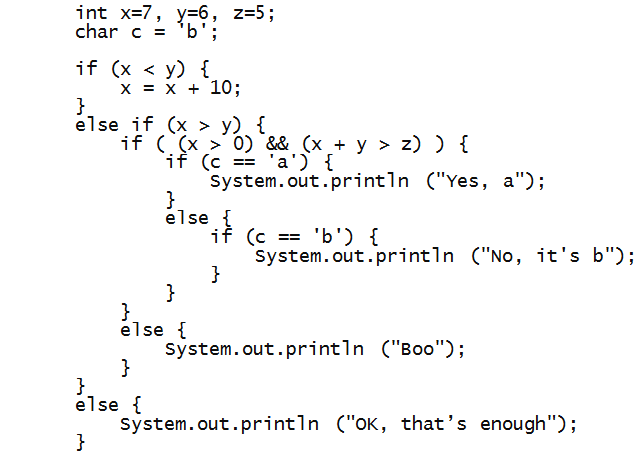

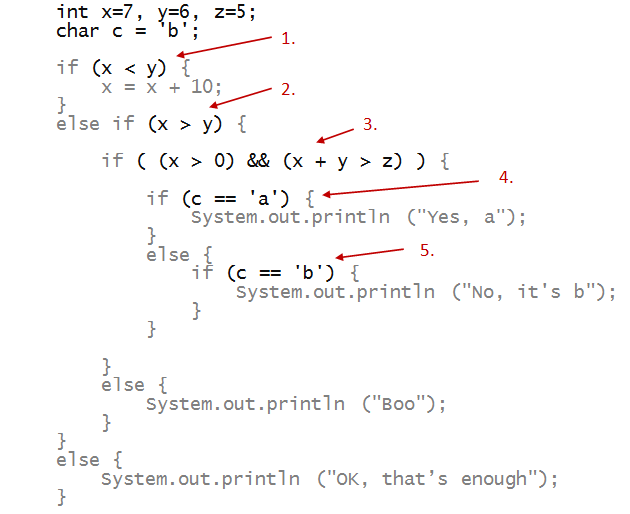

Now let's look at a conditional:

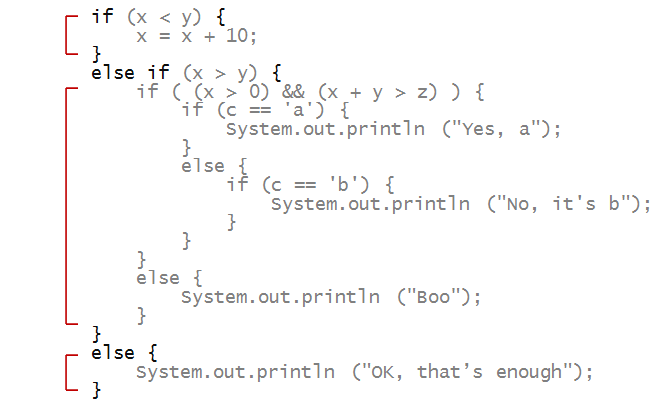

- First, at the outermost level, notice that exactly one of

three blocks will execute:

- For this data, the execution turns out to be:

- First, the Boolean expression (x < y) is evaluated.

=> This fails and goes to the else, which has an if.

- Then, (x > y) is evaluated

=> This turns out to be true, and so, one enters the block inside.

- It so happens that the first statement inside is an if.

=> The complex conditino turns out to be true.

- Then, (c == 'a') is evaluated.

=> Which turns out to be false.

- The else block is entered. This itself has an if inside.

=> The condition (c == 'b') turns out to be true.

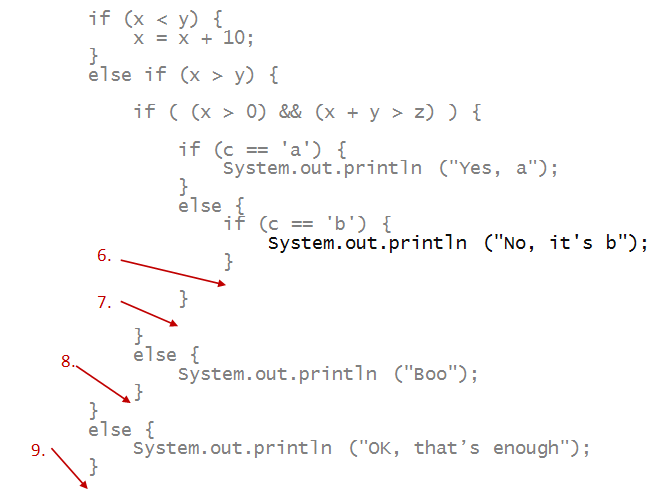

- Now, consider what happens after the println executes:

- The innermost if has no corresponding else

=> Execution continues after the if-block (just past the

closing brace).

=> There's nothing there, so we come out of the else

corresponding to (c == 'a').

- There's nothing there, so we're done with the if-block

with the complex condition.

=> This means we jump past the corresponding else.

- There is nothing to execute here, so we are done with the

if-else with the complex condition.

=> We jump out of the code block corresponding to (x > y).

- Finally, we jump past the outermost if-elseif-else block.

In-Class Exercise 1:

Add println's at places numbered 6-9 above. Make these

print the numbers 6, 7, 8, and 9.

Then, add println's just after the conditions corresponding

to 1, 2, and 3 (to print these numbers).

Did the output correspond to the flow of execution?

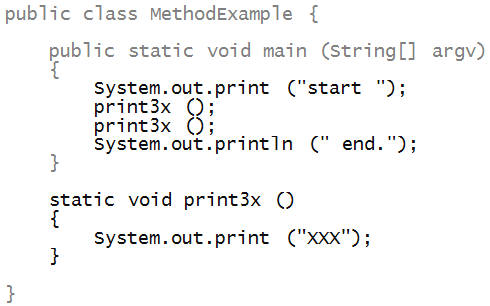

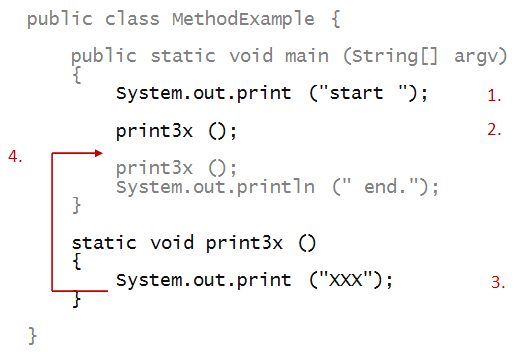

Parameterless methods

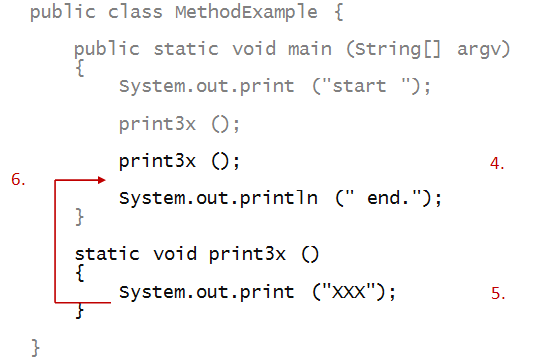

Consider this simple example:

- First, remember that execution always starts at the

first line in main.

- Recall that a method is defined once, but can

be invoked several times (as above).

- Let's trace execution up through the first invocation:

- Execution up through just before the method.

- Then the method call.

- Inside the method.

- When the method completes execution, we return

to the line just after the method call.

- The second call is similar:

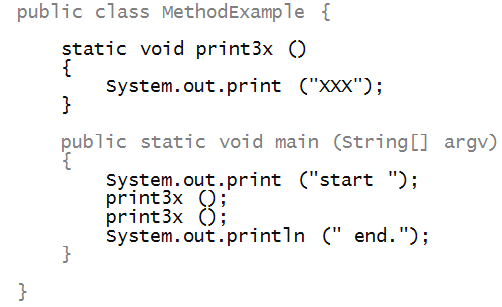

- Note: methods can be declared before invocation.

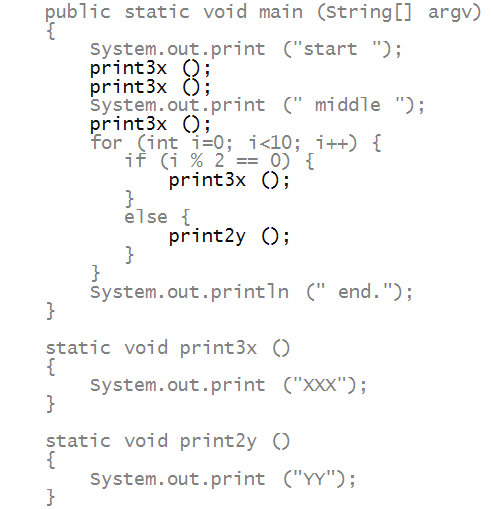

- Methods can be invoked any number of times, in

various places:

In-Class Exercise 2:

Without executing the above program, what is the output?

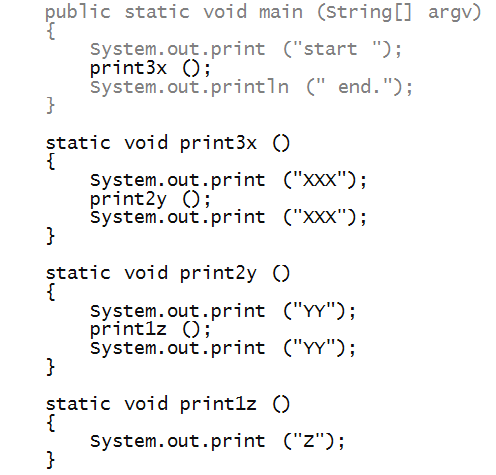

Methods can call other methods:

In-Class Exercise 3:

What is the output of the above program?

Where is System.out.print called for the 5th time?

Methods with parameters

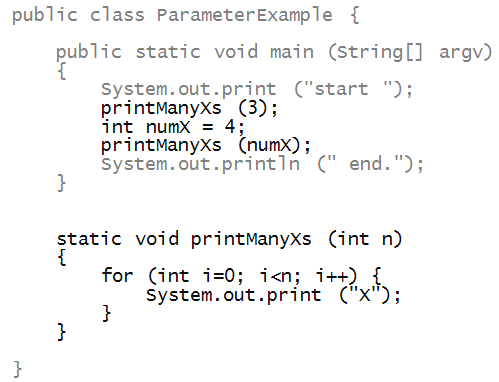

Here's an example of defining and invoking a method

with a parameter:

In-Class Exercise 4:

What is the output of the above program?

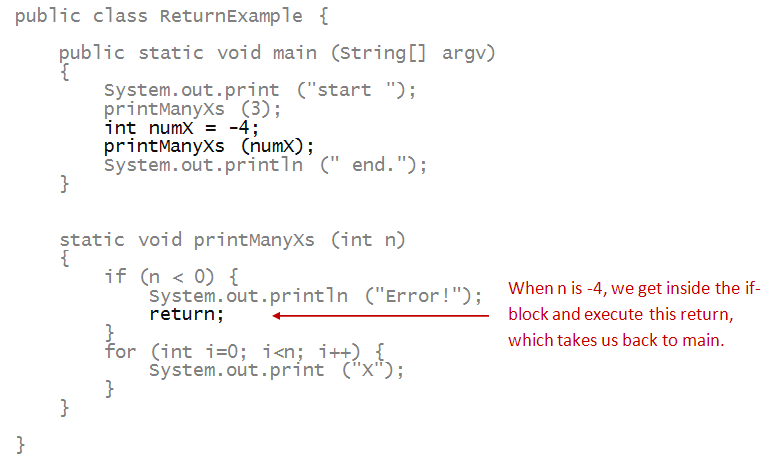

The return statement

First, let's look at methods that don't return a value.

- Remember this: every method returns.

=> It's just that a return at the end is unnecessary.

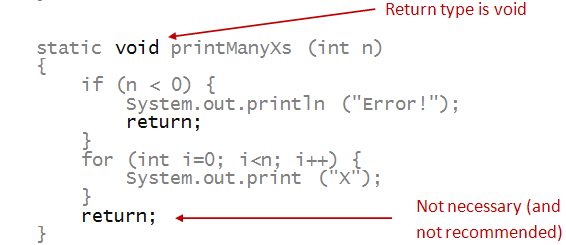

- One could, even if it's redundant, write:

- Notice that no value is returned.

=> This is why the return type is void

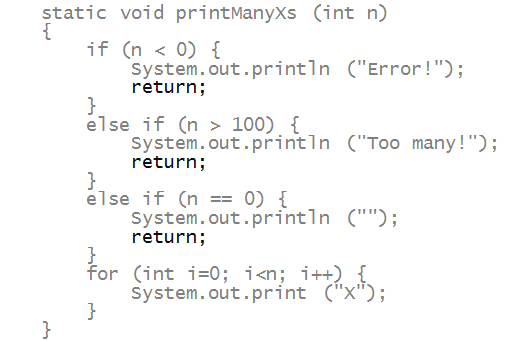

- A method can have any number of return statements:

In-Class Exercise 5:

Without executing it, what is the output of the following program?

public class ReturnExercise {

public static void main (String[] argv)

{

printXsAndYs (3, 4);

printXsAndYs (4, 1);

printXsAndYs (-1, 1);

printXsAndYs (4, -1);

}

static void printXsAndYs (int m, int n)

{

System.out.print ("start ");

if (m < 0) {

// 1.

return;

}

else if (m > 10) {

// 2.

return;

}

for (int i=0; i<m; i++) {

System.out.print ("X");

printYs (n - i);

}

System.out.println (" end.");

}

static void printYs (int k)

{

if (k < 0) {

// 3.

return;

}

else if (k > 10) {

// 4.

return;

}

for (int i=0; i<k; i++) {

System.out.print ("Y");

}

}

}

Write some println's where the numbered comments are to

help you see how the program executes.

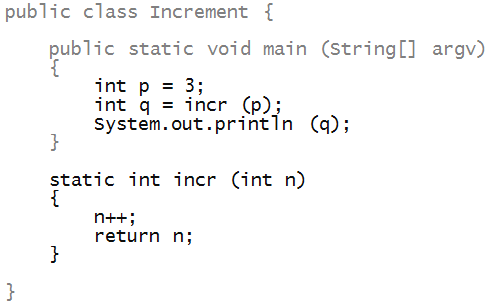

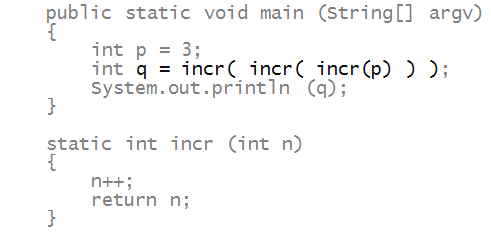

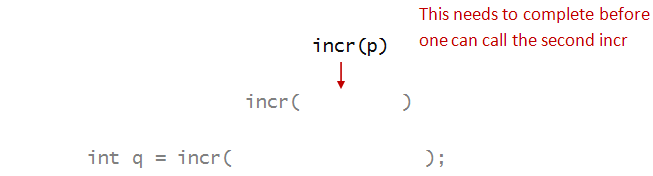

Methods that return a value

Here's a simple method that returns an int:

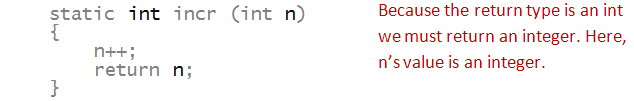

- Notice that the return type is now declared as an int:

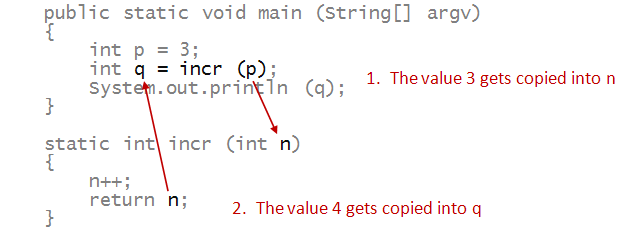

- After execution, the return statement causes the value of

n to be assigned into q

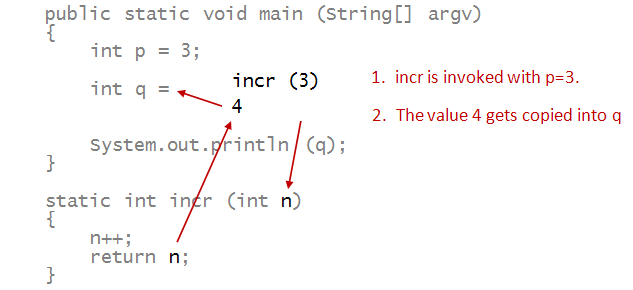

- For purposes of understanding, it might help to visualize

this as:

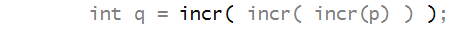

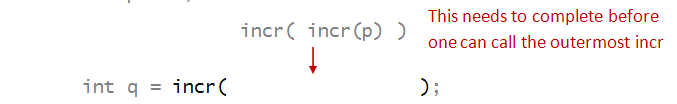

A method call that returns something can be used in

expressions:

- Here, start by looking at the outermost call:

- Then, say to yourself "Oh, the parameter itself

is a method call, which will need to complete to get

the value".

- But that is itself a method call:

In-Class Exercise 6:

Insert a println into the incr method to see

the order of execution.

In-Class Exercise 7:

Without execution, evaluate the output of the code below:

int p = 3;

int q = incr( incr(p) + incr(2) );

int r = incr( incr(q) / p );

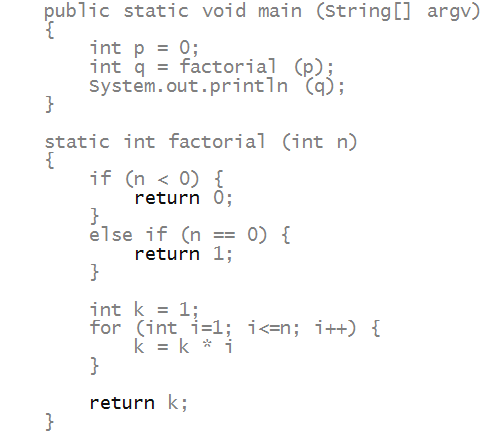

One can have multiple return statements in a

method. Only one will actually execute in a particular

invocation:

In-Class Exercise 8:

Which return statement gets executed above?

Add one println before each return in

factorial. Then, try this code in main:

int p = 3;

int q = factorial (factorial(p)) * factorial(p-3) + factorial (-3);

In-Class Exercise 9:

The program below has three errors. Can you see them

without compiling the program? Fix the errors.

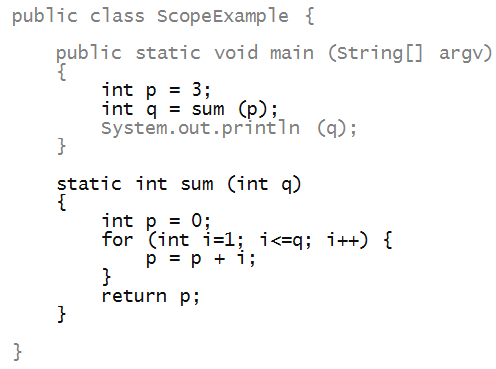

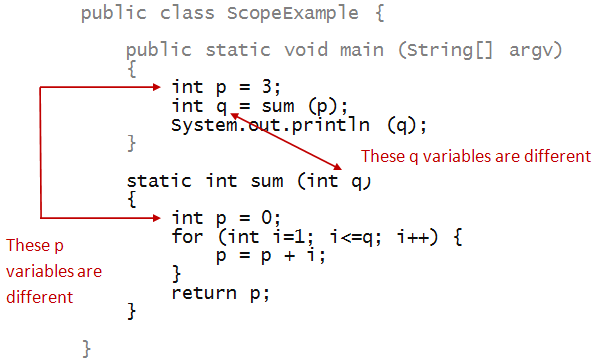

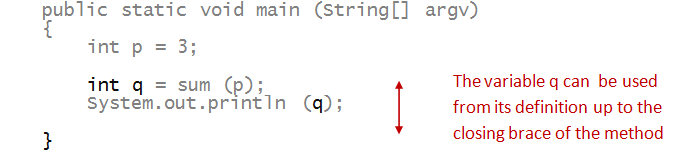

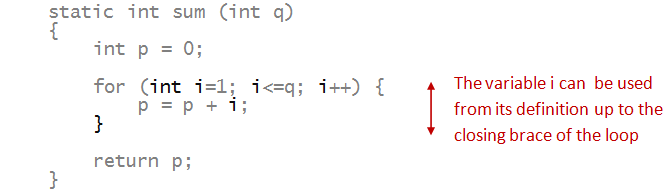

Scope

Consider this program:

- First, note that the there are two different

p and q variables:

- The scope of a variable is the body of code that's

allowed to access (or use) the variable.

- For example:

- Likewise ...

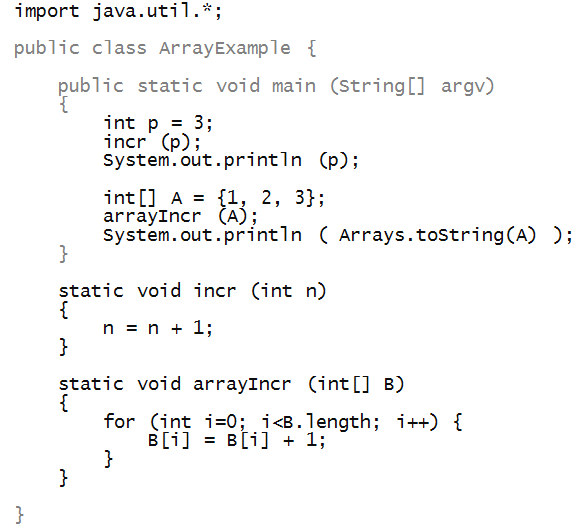

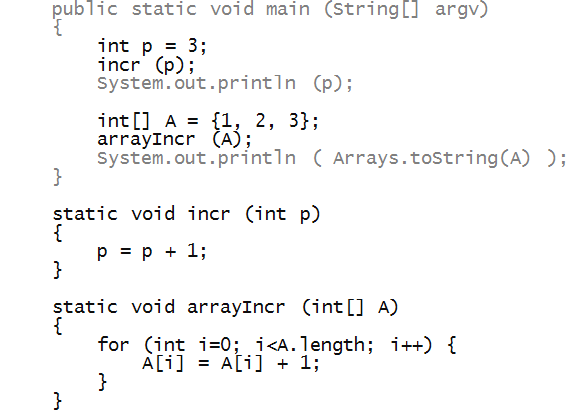

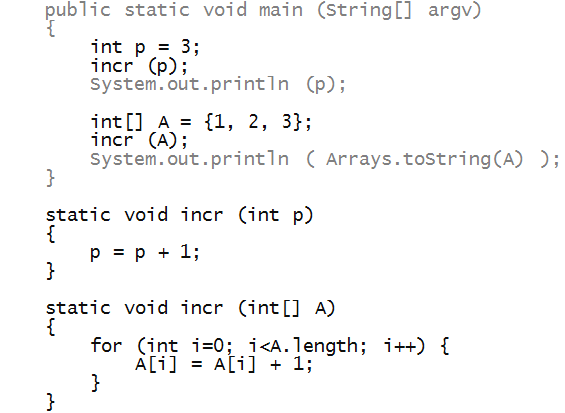

Arrays are different

Consider this program:

- Here, the output is:

3

[2, 3, 4]

Thus, the variable p is not affected by the call to incr

whereas the array A certainly is.

- Arrays are fundamentally different from basic types.

- When an array is passed as parameter, it is passed as

a so-called reference

=> This means the invoked method has access to the array, and can modify its contents.

- This stays true no matter how the variables are named:

- An aside: methods that have different signatures can use

the same name:

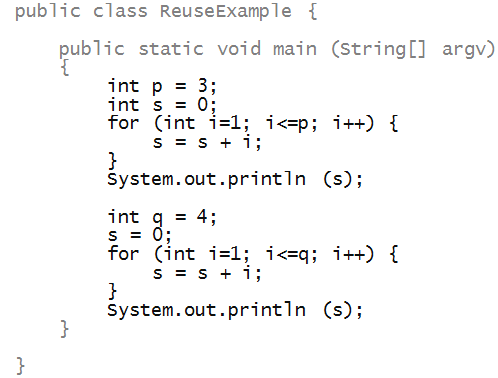

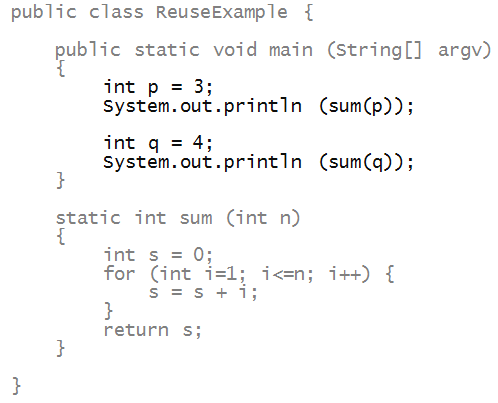

Why we use methods

Methods are very useful for four different reasons:

- Code written in a method can be re-used.

For example, compare

with

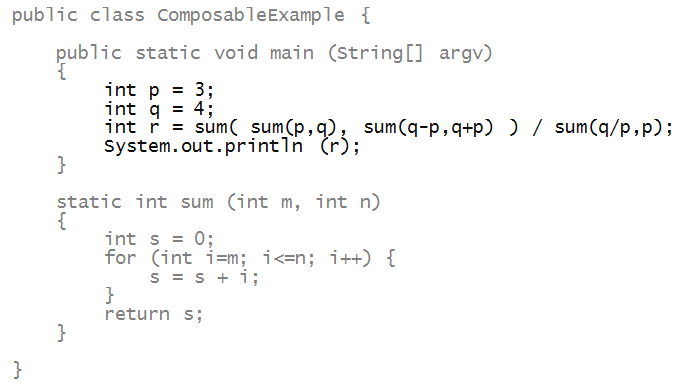

- The second big reason is composability,

as this example shows:

- A long program broken up into methods will make

the program more readable and therefore more easily understood.

- The biggest reason, perhaps, is that it has become one

of two important ways by which multiple programmers

use each others' code.

Example: you have used methods in DrawTool,

and Java library methods like Math.random().

How do you know when to create methods vs. writing long code?

- There are no rules. This comes by practice.

- Generally, tiny computations like increment don't

need methods.

- Any significant computation that is likely to be

re-used should probably be in a method.

- Use methods when breaking things into methods greatly

improves readability.