A Survey with ED Perspective

Draft 1.0

Table of Contents

1.3.1 Variety of Basic Metadata 7

1.4.1 Details of Advanced Metadata 8

1.4.2 HTML, XML, RDF, RSS etc. 11

1.4.4 CMS – Content Management System 14

2 Functional Metadata Classes 15

Metadata is often called data about data or information about information. Metadata is structured information that describes, explains, locates, or helps to retrieve, use, or manage an information resource.

Metadata is used differently in different areas. Metadata schemes have been developed to describe various types of textual and non-textual objects including books, e-documents, art objects, educational and training materials, and scientific datasets.

So far, most of the involvement of ED with metadata has to do with metadata of documents such as: text documents, spreadsheets, emails, databases, etc. We call such use basic. More advanced forms of ED require discovery from digital libraries, e-commerce, web services, etc. is sure to become important in ED. We call such use advanced.

NISO, the National Information Standards Organization, defines three types of metadata1:

Descriptive metadata describes a resource for purposes such as discovery and identification. It can include elements such as title, abstract, author, and keywords.

Structural metadata indicates how compound objects are put together, for example, how pages are ordered to form chapters.

Administrative metadata provides information to help manage a resource, such as when and how it was created, file type and other technical information, and who can access it. There are several subsets of administrative data; two are:

Rights management metadata, which deals with intellectual property rights, and

Preservation metadata, which contains information needed to archive and preserve a resource.

Metadata can describe resources at any level of aggregation. It can describe a collection, a single resource, or a component part of a larger resource. Metadata can be embedded in a digital object or it can be stored separately. Metadata is external to Word documents, often embedded in HTML documents and in the headers of image files.

Note that NISO’s classification reflects usage of the metadata. It classifies the metadata according to the information they contain. Other classifications are feasible as well. Later on in this write-up, we will present other classifications.

At the very beginning of the 21st Century, ED’s metadata focus is on widely used documents. In other words, ED focuses on articles, memos, emails, data files, databases and web pages. We divide the discussion of metadata to basic and advanced metadata. We believe that basic metadata is in the mainstream of ED works these days. Advanced metadata represents several aspects of metadata that:

Are not frequently topics of legal discovery. These data may be application domains less frequently encountered, rarer document formats and newer technologies.

Both ED and metadata make fast advances these days. That causes a discrepancy between ED focus and what metadata covers.

ED experience has not yet reached the complexity and depth needed to cover areas such as digital libraries, complex Web applications and search metadata.

Still, ED is bound to cover all of metadata developments as the need arise. Presenting the area justification is there.

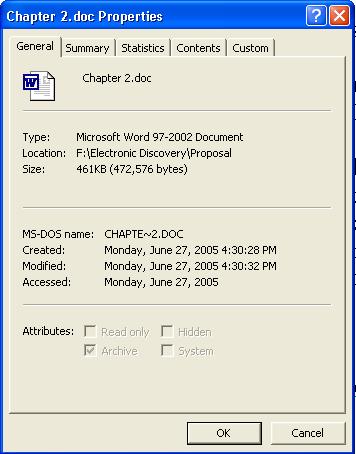

Metadata is data that is automatically created and stored by computer programs that is not part of the content of the document. Embedded data is metadata, which is “definitional data that provides information about or documentation of other data managed within an application or environment2.” For example, word processing programs store information about when data files are created and when, and who accesses them. The figure below is an example of some metadata of the document this text appears in. In shows the following items that are not part of the file content:

Document name

File location

Size

Creation, modification and last access times

Attributes of different kinds

Microsoft Office documents, which play a central role in today’s basic infrastructural documents, automatically store information, i.e. metadata, about the individual working on the documents, her firm, her network and each time your create or access a document file.

The following are most of metadata information found in a typical Word or Excel document:

Author's name and initials

Author's organization name

Server name on which the document is stored

File properties/summary information

Non-visible portions of embedded OLE objects

Previous author's names and initials

Document revisions

Document versions

Template details

Hidden text

Hidden Cells

Comments

Smart Tags

Network and World Wide Web links

Word’s Object Linking and Embedding (OLE) capabilities allows placing a presentation slide or cells from an Excel worksheet into a document, and Word associates that object with the program used to create it3. Embedded Objects in Documents May Contain Metadata. If you embed an object in a document, the object retains its own properties, regardless of what you do to the document. For example, if you embed a Microsoft Excel workbook in a Word document, the document and the workbook each has its own properties.

Microsoft's Smart Tags4 allow items in Word docs, spreadsheet cells and other Office applications to have properties attached to them. For example, a person's name in the document could have knowledge of its entry in a address book, or as the author of a book, or as a family member in some file. Tags may have multiple associations of this sort.

Working with an item with Smart Tags attached to it, the individual is presented with a number of options for actions to be taken in association with it. Conceivably, the actions could be automatically carried out. The action can apply to multiple targets the number of which is unlimited. Smart tags, therefore, have great potential. These tags are a great mechanism for automating connections between different files based on different applications. As metadata and for discovery such complex and rich source may be a God’s send.

Smart Tags are written in XML5 which is a widely used mark up language used widely by industry for which there are unlimited number of support tools as well as usage.

MS Word, like many other applications, makes use of embedded commands of different kinds. To demonstrate this type of metadata, we start with Field Codes in Word. An example is:

The following field displays a Microsoft Graph object embedded (embed: To insert information created in one program, such as a chart or an equation, into another program. After the object is embedded, the information becomes part of the document. Any changes you make to the object are reflected in the document.) in a document:

{ EMBED MSGraph.Chart.8 \* MERGEFORMAT }6

Embedded commands are small programs that direct the application, in this case the application is Word, to execute a sequence of step to form a fragment of the document. Spreadsheet application may have mathematical function and even small programs embedded in them.

A paper version of the document does not even hint at the existence of such data, but even an electronic version does not show commands unless explicitly asked for.

Metadata is not restricted to documents. Cookies are small text files that are stored on a user's computer by a Web server explicitly permitted to do so by the user's browser software. A cookie itself is not typically read by the user. Rather, it is an identifier used by the Web site that originally placed it on your hard drive. Cookies can contain any arbitrary information the server chooses and are used to introduce state into otherwise stateless transactions.

Due to the centrality of Microsoft Office products in the office setting most discussion of metadata centers around MS Office metadata. Clearly, other products have their own metadata instances and typical use. Adobe documents, PDF, and WordPerfect also have metadata7.

Typically cookies are used to authenticate or identify a registered user of a web site as part of their first login process or initial site registration without requiring them to sign in again every time they access that site. Other uses are maintaining a "shopping basket" of goods selected for purchase during a session at a site, site personalization (presenting different pages to different users), and tracking a particular user's access to a site.

Metadata varies highly; it is growing, changing and requires a detailed understanding and the particular domain to which the metadata applies. Fortunately, discovery will typically cover limited domains and a single domain expert may suffice. This book Metadata in Practice8 provides a background on the world of metadata. It details a wide range of different metadata projects that involve an education digital library, statewide collaboration efforts, museums, university libraries, an image database, geographic data, aggregation, and sharing. It discusses the future of metadata development and practice by exploring its standards, harvesting, reuse, repurposing, and interoperability, among other topics.

Most ED publications dealing with documents focus mainly on textual documents such as: memos, articles, letters, notes, draft documents, manuals, emails, etc. Word processors or simple text editors create such texts. In other words, tools such MS Word, WordPerfect and notepads of different kinds produce these documents. (Typically, email clients, Outlook, Thunderbird, Eudora and etc., embed simple notepads.) We have already mentioned metadata associated with these document formats, but there are potentially other metadata that are less common these days but are being used increasingly with time.

Metadata schemes are sets of metadata elements that describe information resource. Optionally, they may specify content rules for how content must be formulated, representation rules for content and allowable content values. There may also be syntax rules for how the elements and their content should be encoded. Many metadata schemes use SGML (Standard Generalized Mark-up Language) or XML (Extensible Mark-up Language). SGML is a superset of both HTML and XML and allows for the richest mark-up of a document.

|

Dublin Core Example Title=”Metadata” Creator=”Doe, John” Subject=”metadata” Description=”Demonstrate Dublin Core.” Publisher=”XYZ Press” Date=”2005" Type=”Text” Format=”application/doc” Identifier=”http://www.gwu.edu/ ~shmuel/work/What Is Metadata.do ” Language=”en”

|

Many different metadata schemes are being developed in a variety of user environments and disciplines. Some of the most common ones are discussed in this section.

Dublin Core

The original objective of the Dublin Core was to define a set of elements that could be used by authors to describe their own Web resources. The 15 core elements are: Title, Creator, Subject, Description, Publisher, Contributor, Date, Type, Format, Identifier, Source, Language, Relation, Coverage, and Rights. The Dublin Core is simple and concise, and designed to describe Web-based documents. However, Dublin Core has been used with other types of materials and in applications demanding some complexity.

All Dublin Core elements are optional and all are repeatable. The elements may be presented in any order. While the Dublin Core description recommends the use of controlled values for fields where they are appropriate (for example, controlled vocabularies for the Subject field), this is not required. Because of its simplicity, the Dublin Core element set is now used by many outside the library community— r e s e a r c h e r s, museum curators, and music collectors to name only a few.

In addition to the Dublin Core, several more initiatives try to fill the needs for metadata by different application domains.

The Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) is an international project to develop guidelines for marking up electronic texts such as novels, plays, and poetry, primarily to support research in the humanities.

The Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard (METS) was developed to fill the need for a standard data structure for describing complex digital library objects. METS is an XML Schema for creating XML document instances that express the structure of digital library objects.

The Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) is a descriptive metadata schema that is a rich description of electronic resources which provides some advantages over other metadata schemes. MODS elements are richer than the Dublin Core; its elements are more compatible with library data than the ONIX or Dublin Core standards.

Metadata schemas are increasingly being developed to support electronic commerce applications. The <indecs> Framework (Interoperability of Data in ECommerce Systems) was an international collaborative effort of publishers and members of the recording industry, who wanted to develop a framework for metadata standards to support network commerce in intellectual property.

The foundation of the <indecs> work is a data model for intellectual property and its transfer. Rather than developing a new metadata scheme, <indecs> sought to develop a common framework to allow various schemes for transactions related to different genres such as music, journal articles, and books to be able to interchange information, particularly that related to intellectual property rights. In order to support this common framework, <indecs> has developed a minimal kernel of required metadata.

Metadata used to describe visual objects such as a painting or sculpture has its own special requirements. The Art Information Task Force (AITF) developed a framework for describing and accessing information about objects and images called Categories for the Descriptions of Works of Art (CDWA). Some 30 categories were defined, most with multiple subcategories. Examples of the specialized descriptive elements relevant to artworks included are: Orientation, Dimensions, Condition, Inscriptions, Conservation Treatment, and Exhibition / Loan History.

VRA Core Categories build on and expand the CDWA work to define a single metadata element set that can be used to describe the work (the actual painting, photograph, sculpture, building, etc. ) as well as the images (visual representations) of them. Both CDWA and VRA emphasize the use of controlled vocabularies for specified elements.

The ISO/IEC Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG) has developed a suite of standards for coded representation of digital audio and video. Two of the standards address metadata: MPEG-7, Multimedia Content Description Interface (ISO/IEC 15938), and MPEG-21, Multimedia Framework (ISO/IEC 21000). MPEG-7 defines the metadata elements, structure, and relationships that are used to describe audiovisual objects including still pictures, graphics, 3D models, music, audio, speech, video, or multimedia collections. It is a multipart standard that addresses:

Description Tools including Descriptors that define the syntax and the semantics of each metadata element and Description Schemes that specify the structure and semantics of the relationships between the elements.

A Description Definition Language to define the syntax of the Description Tools, allow the creation of new Description Schemes, and allow the extension and modification of existing Description Schemes.

System tools, to support storage and transmission, synchronization of descriptions with content, and management and protection of intellectual property.

A new generation of documents based on markup languages, data description and style formats is already used in many applications. Web pages are mostly written in HTML, which stands for Hyper Text Markup Language. A simple example clarifies both HTML and the basic notion of markup. To display EXAMPLE in HTML one writes <B>EXAMPLE</B>. Where < and > indicate a markup, i.e. formatting instruction, B indicates Bold. With enough markup variety one can use a markup language to do everything a typical word processor does.

When viewing Web pages one does not see the markup unless it is asked for explicitly. A markup is an executable form of metadata. This metadata has its own metadata. HTML uses Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) that are style sheet language used to describe the presentation of a document written in a markup language. CSS is used to define colors, fonts, layout, and other aspects of document presentation. CSS is the metadata of HTML while HTML is the metadata of the Web page document. Different style sheet will render different colors, fonts and basically change the visual depiction; the content is not affected.

Technically HTML markup is itself metadata, it appears of limited interest for legal purposes. Yet, HTML has a comment markup, e.g. <!-- Hello -->. However, instead of Hello is may say: <!—copyright by ACD Inc. --> and ACD happens the requestors’ client. In other words, this metadata is the smoking gun!

XML stands for Extensible Markup Language. Wikipedia states that XML

“is a W3C-recommended general-purpose markup language for creating special-purpose markup languages, capable of describing many different kinds of data…. Its primary purpose is to facilitate the sharing of data across different systems, particularly systems connected via the Internet. Languages based on XML (for example, Geography Markup Language (GML), RDF/XML, RSS, MathML, XHTML, SVG, MusicXML and cXML) are defined in a formal way, allowing programs to modify and validate documents in these languages without prior knowledge of their form.”

RDF, RSS, WSDL and similar languages are applications of XML. For example (from Wikipedia): Resource Description Framework (RDF) is a family of specifications for a metadata model that is often implemented as an application of XML.

The RDF metadata model is based upon the idea of making statements about resources in the form of a subject-predicate-object expression, called a triple in RDF terminology. The subject is the resource, the "thing" being described. The predicate is a trait or aspect about that resource, and often expresses a relationship between the subject and the object. The object is the object of the relationship or value of that trait.

In summary, RDF is resources metadata; it describes the resources. Same way we RSS, which depending on the version Rich Site Summary or RDF Site Summary or Really Simple Syndication, and allows users to subscribe to websites that have provided RSS feeds; these are typically sites that change or add content regularly. RSS may replace periodic emails such as a daily result of a search you perform.

RSS, therefore, is the metadata of data syndication. At the same time, this metadata data, i.e. RSS, may have its own metadata. For example: Creative Commons9 adds a tag to the RSS that is essentially metadata of metadata. The tag starts with <creativeCommons:license>.

Many documents are singletons. Such documents may be related through topics, date, version or source, but each is saved separately and independently of the others. For instance, when counsel takes depositions of several witnesses, each deposition record is totally independent of the other records. The depositions are related by the case under hand, some witness may cover overlapping areas, etc.

Above we mentioned NextPage as a revision control application. Here is what Wikipedia says about revision control:

Revision control is an aspect of documentation control wherein changes to documents are identified by incrementing an associated number or letter code, termed the "revision level", or simply "revision". It has been a standard practice in the maintenance of engineering drawings for as long as the generation of such drawings has been formalized. A simple form of revision control, for example, has the initial issue of a drawing assigned the revision level "A". When the first change is made, the revision level is changed to "B" and so on.

Revision control (RC) maintains detailed information about the documents it contains and on the revisions made to them. This is metadata. Since this metadata pertains to document that already have simple metadata, this metadata augments that original one. We list some common metadata records maintained by a revision control application:

Time and date document entered RC first time, which is later than the document creation time

Time and date when was document changed

Commentary for change (e.g. reason, nature of change, supervisor of change) Change itself

A complete history of changes to document

Documents may be grouped together into “projects,” which have their own metadata

Some example of project metadata that is (or could be) persisted in the project directory are:

Project nature and users

Launch configurations – how to use the documents

Document manipulating application (e.g. MS Word)

Tasks/Bookmarks

File encodings

Dead documents

The metadata maintained by RC contains way more information that the individual document contains. Most striking is the fact that RC may provide not only creation, modification and last access dates for a document, but also any access to the data, all the changes and who made them. That is a substantial history of a document.

Wikipedia says:

A content management system (CMS) is a system used to organize and facilitate collaborative creation of documents and other content. A CMS is frequently a web application used for managing websites and web content.

CMS allow authors to provide new content in the form of articles. The articles are typically entered as plain text, perhaps with markup to indicate where other resources (such as pictures) should be placed. The system then uses rules to style

the article, separating the display from the content, which has a number of advantages when trying to get many articles to conform to a consistent "look and feel". The system then adds the articles to a larger collection for publishing.

The nouns italicized are metadata. CMS also has workflow, approval of changes record, session logs, templates and a lot of the RC metadata.

Again, CMS augments each document’s metadata substantially.

Digital libraries are heavily used by universities, states and the Library of Congress. A digital library is a collection of documents. The table of core metadata elements for library of congress digital repository has more than 50 elements. Some digital library tools are already available and sooner or later the commercial world will start using it.

RC and CMS are commonplace. The detailed mention of them is useful because one will encounter them frequently doing ED. But there are many other many other applications in use with the functionality to create “projects” – families of documents – and enhance the amount of metadata available.

Some generic applications that come to mind are:

Integrated (software) development Environments – for software development

(Software) Testing tool

Simulation application

Weblog tool – for running weblogs

Photo album software

We have used the generic name of the applications. In reality one uses a product, commercial or public domain that deviates from the generic application. Deviations are typically minor additions, omissions and changes.

The following are several metadata classification approaches based on the functionality of the metadata, its state and its goals.

Syntactic vs. Semantic

Use vs. Search

Static vs. Dynamic

State vs. Persistent

Syntactic metadata describes non-contextual information about content, focusing on elements such as size, location or date of document creation providing little or no contextual understanding of what the document says or implies. This level of metadata is often the extent of many content management technologies.10

Semantic metadata: Metadata that describes contextually relevant or domain-specific information about content (in the right context) based on a domain specific metadata model (e.g. industry-specific or enterprise specific) or ontology is known as semantic metadata. For example, if the content is from the business domain, the relevant semantic metadata could be company name, ticker symbol, industry, sector, executives, etc., whereas if the content is from the Intelligence domain, the relevant semantic metadata could be terrorist name, event, location, organization, etc. Metadata that offer greater depth and more insight ‘about the document’ fall under the semantic metadata category.

Assuming data has elements of time and latitude/longitude. The type of data can be expressed by syntactic metadata. Semantic descriptions for time and Lat/Lon can be embedded within the syntactic metadata. For time, it may provide the start time and time format. Lat/Lon can be provided as degrees or radian. The semantic metadata can also provide capabilities to define equation for data conversion.

Use metadata is what a computer would be able to take advantage of in presenting and processing data. Search metadata11 is what a person would be interested in looking at, in order to decide if there are things of interest in a data set.

A developer may enable Windows Vista to access the content and metadata of her application files by writing a property handler that implements Windows Vista search metadata management interfaces. Windows Vista Explorer uses these property handlers to search and display your application metadata.

Static metadata doesn't change much over the life cycle of the data it describes. Dynamic metadata12 is a function of the data; as the data changes, so does the dynamic metadata.

For example, there is a method for adding dynamic metadata to multimedia data, based on the emerging MPEG-7 standard. The method enables metadata be dynamically added, removed, altered or processed in generic way. By creating objects and interfaces, the content creator can add functionality to the metadata.

State metadata captures the state of something (a system, a component, a data set) at a given time or time range. Persistent metadata describes a system, component, or data set that either does not changes or between changes (e.g. a back of the data).

An executing object has several sets of metadata:

A meta-object based on the reflective object model

An executing context (files, ports, etc.)

Current state (variable values, buffers, etc.)

At any moment in time, all three metadata sets together constitute the state metadata. When the object is not executing (e.g. dormant, suspended, kept on disk until further notice, etc.) the same sets constitute the persistent metadata.

1 NISO Press, National Information Standards Organization, Understanding Metadata, ISBN: 1-880124-62-9, 2004.

2 Dictionary.com, http://dictionary.reference.com/search?q=metadata

4 Darshan Singh, Integrating Office XP Smart Tags with the .NET XML Web Services, e-doc (Adobe Reader), Apress; ISBN: B0007MHF54; (May 20, 2002)

5 Elliotte Rusty Harold and W. Scott Means, XML in a Nutshell, Third Edition, O'Reilly; (September, 2004)

6 MicroSoft Word Help file.

7 Donna Payne, Metadata – Are You Protected? Payne Consulting Group, 12/7/2004.

8 Diane I. Hillmann and Elaine L. Westbrooks (Editors), Metadata in Practice, American Library Association (June 1, 2004)

9 Creative Commons, http://creativecommons.org/

10 A. Sheth, “Changing Focus on Interoperability in Information Systems: From System, Syntax, Structure to Semantics”, in Interoperating Geographic Information Systems. M. F. Goodchild, M. J. Egenhofer, R. Fegeas, and C. A. Kottman (eds.), Kluwer, Academic Publishers, 1999, pp. 5-30.

12 Boris Rogge, Rik Van de Walle, Ignace Lemahieu, Wilfried Philips. "MPEG-7 BASED DYNAMIC METADATA," icme, p. 279, 2001 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME'01), 2001.