1

The Difference between Electronic and Paper Documents

In

content, electronic documents are no different than paper documents.

All sorts of documents are subject to discovery electronic or

otherwise. Legally and technically, there are substantial differences

between the discoveries of the two media.

“Some

93 percent of documents are now created electronically, according to

industry reports. And 70 percent of documents never migrate to

paper.”

No matter what the legal status of discovery of electronic documents

will be, the prevalence of electronic documents makes them a major

discovery issue.

The

following is a list of discovery-related differences between

electronic documents and paper ones. We assume that a paper document

is a document that was created, maintained, and used on actual paper;

it is not a hard copy of an electronic document.

1.1 The magnitude of

electronic data is way larger than paper documents

T his

point is obvious to the majority of observers. Today’s typical

disks are at several dozens gigabytes and these sizes grow

constantly. A typical medium-size company will have PC’s on the

desks of most white-collar workers, company-related data, accounting

and order information, personnel information, a potential for several

databases and company servers, an email server, backup tapes, etc.

his

point is obvious to the majority of observers. Today’s typical

disks are at several dozens gigabytes and these sizes grow

constantly. A typical medium-size company will have PC’s on the

desks of most white-collar workers, company-related data, accounting

and order information, personnel information, a potential for several

databases and company servers, an email server, backup tapes, etc.

Such

a company will easily have several terabytes of information.

Accordingly,

such a company has over 2 million documents. Just one personal hard

drive can contain 1.5 million pages of data, and one corporate backup

tape can contain 4 million pages of data. Thus the magnitude of

electronic data that needs to be handled in discovery is staggering.

In most corporate civil lawsuits, several backup tapes, hard drives,

and removable media are involved.

1.2  Variety of electronic documents is larger than paper documents

Variety of electronic documents is larger than paper documents

Paper

documents can be ledgers, personnel files, notes, memos, letters,

articles, papers, pictures, etc. This variety exists also in

electronic form. But then spreadsheets are way more complex than

ledger, for example. They contain formulas, may contain charts, they

can serve as databases, etc. In addition to the additional

information, e.g. charts, the electronic spreadsheet supports

experimentation with what-if version the discoverer may want

to investigate.

To

demonstrate the variety possible in electronic documents it

sufficient to consider the most ubiquitous of them: the text

document. A Word

document may contains:

An active spreadsheet

Charts

Pictures

Audio

components

Video

clips

Links

to Web address

Proliferation

of new devices such as Personal digital assistants, pocket PCs, palm

devices and BlackBerry devices adds more variants of electronic

documents and increases the responsibility of discovery.

1.3 Electronic

documents contains attributes lacking in paper documents

C omputers

maintain information about your documents, referred to as “metadata,”

such as: author’s name, document creation date, date of it last

access, etc. A hard copy of the document does not reveal metadata,

although certain metadata items may be printed. Depending on what you

do with the document after opening it on your computer screen, the

actions taken may change the metadata collected about that document.

Paper documents were never that complex.

omputers

maintain information about your documents, referred to as “metadata,”

such as: author’s name, document creation date, date of it last

access, etc. A hard copy of the document does not reveal metadata,

although certain metadata items may be printed. Depending on what you

do with the document after opening it on your computer screen, the

actions taken may change the metadata collected about that document.

Paper documents were never that complex.

Text

documents allow you to pick fonts, use colors, use shade selectively,

use watermark and change the background and text. Spreadsheets allow

one to selectively display rows and columns, hide formulae and write

complex macros. Many other document types have similar and additional

attributes you may employ.

Attributes

such as hiding parts of the document are significant to discovery

that may tries to be informed about the hidden parts.

1.4 Electronic documents are more efficient than paper documents

D ocument

efficiency is not a standard term. Here, Document Efficiency means

factors such as:

ocument

efficiency is not a standard term. Here, Document Efficiency means

factors such as:

Use of less space

Easier to change

Cost of delivery

Faster to search

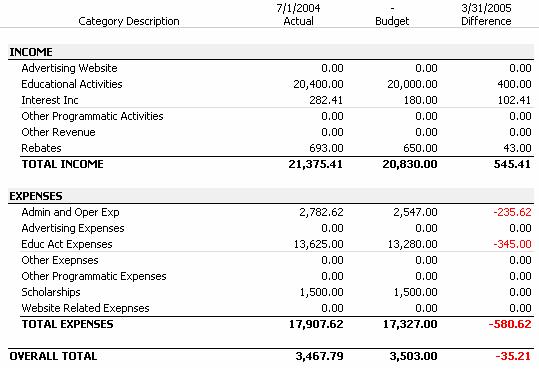

|

Factor

|

Electronic

|

Paper

|

|

Space

|

Personal file systems are

physically smaller than a small cell phone

|

stored locally in filing

cabinets

|

|

Ease of change

|

can be edited, copied,

modified and merged with almost complete ease

|

requires in most cases

recreating document all over again

|

|

Delivery speed and cost

|

by networks, disks, flash

memory and CD/DVD

|

by mail or manually

|

|

Search/access

|

multiple users may access

documents simultaneously

|

multiple users to access

documents simultaneously one needs a set of documents per each

accessing person

|

1.5 The structure

of electronic documents may reach complexity absent from paper

documents

D ocument

complexity is used quite widely in literature and industry. Recent

work deals mainly with XML documents that do not directly pertain to

this discussion. The presentation

fits our needs. Documents complexity is the sum of item

complexity and format complexity.

ocument

complexity is used quite widely in literature and industry. Recent

work deals mainly with XML documents that do not directly pertain to

this discussion. The presentation

fits our needs. Documents complexity is the sum of item

complexity and format complexity.

Item

complexity is defined as the sum of items within a complex document.

An item is discrete, discernable object associated with a document.

For example, the abstract, the content table page, multiple content

pages, and additional items like photographs, audio and video.

Format

complexity is defined as the sum of all formats within a complex

document. A unitary format document contains only one type of file

encoding. A binary format document contains two types of file

encoding.

There

are other ways to define document complexity,

but the one above approach works well for us.

Using

the document complexity make abandonedly clear that electronic

documents have more items and more formats and, therefore, are more

complex.

1.6 Electronic

documents are more persistent and more difficult to destroy than

paper documents

P aper

documents are easy to destroy. They may be throwing away, shredding,

burned, lost or stolen. Once such acts take place the documents

disappear. Deleting an electronic document eliminates only the

ubiquitous accessible copy. The document, i.e. its data, still exists

and in systems such as Windows and Mac OS, an accessible reference to

deleted documents may be in the trash bin. Restoring a document in

the trash bin, i.e. a deleted document, revives the document to its

original glory.

aper

documents are easy to destroy. They may be throwing away, shredding,

burned, lost or stolen. Once such acts take place the documents

disappear. Deleting an electronic document eliminates only the

ubiquitous accessible copy. The document, i.e. its data, still exists

and in systems such as Windows and Mac OS, an accessible reference to

deleted documents may be in the trash bin. Restoring a document in

the trash bin, i.e. a deleted document, revives the document to its

original glory.

Even

removing the document from the thrash bin does not erase the

documents data off the disk. Once removed from the thrash bin,

documents data areas on the disk go into a “fee list”

that makes those areas available for future data creation needs. The

free list contains all areas not currently allocated to active

documents as well as to deleted documents still in the trash bin. How

long will an area stay on the free list (thereby still containing the

deleted documents data)? That is difficult to predict due the huge

variability of factors such as: future demand for disk space, size of

current and future files, the current availability of disk space,

etc.

Even

the complete deletion of a document, its trash bin instance and the

allocation of the document’s data area on the disk does not

typically extinguishes the document altogether. Certain habitual

practices create copies of documents and are only marginally affected

by document deletion:

Backups – most

organizations and individuals regularly create back up copies of

documents as precautionary actions. The backups are maintained

independently of the document itself.

Documents may be exchanged by

email, access through web pages and manually handed electronic

copies. Thus copies continue to exist after the deletion of the

original document.

Even work on a simple text

document is quite frequently preceded by creating a copy of the

document being edited. Once again, such copies persist beyond the

deleted document unless specifically deleted.

1.7 Electronic

documents change faster, more frequently and easier than paper

documents

C hanges

to an electronic document are fast and easy. The reason is obvious;

all you need to do is make the change and save it. Changes to paper

documents, however, require retyping the whole document.

hanges

to an electronic document are fast and easy. The reason is obvious;

all you need to do is make the change and save it. Changes to paper

documents, however, require retyping the whole document.

There

are many other reasons to the difference in speed and frequency. We

already said that documents may be dynamic. Web pages are made

dynamic in order to ease change.

For

discovery, faster and frequent changes imply a need for a more

meticulous and length monitoring of document discovery.

1.8 Electronic

documents last longer than paper documents

P aper

deteriorates with time; paper documents can be destroyed by flood and

fire. Although these factors have their parallels in electronic

documents, e.g. a flooded computer loses its data; typical backups of

the documents practices maintain copies away from the “office.”

Paper documents may enjoy the same treatment, but the frequency,

extent and usage of such backups is substantially lower.

aper

deteriorates with time; paper documents can be destroyed by flood and

fire. Although these factors have their parallels in electronic

documents, e.g. a flooded computer loses its data; typical backups of

the documents practices maintain copies away from the “office.”

Paper documents may enjoy the same treatment, but the frequency,

extent and usage of such backups is substantially lower.

Electronic

document suffer from upgrades in technology. If one used a peculiar

word processor, e.g. WordStar, to write a document 20 years ago,

today it will be difficult to convert the document to current word

processor, but a tool to convert the document can be located. Same

holds for spreadsheets, databases, etc. Again, most companies have

practices that avoid such problems by evolving documents with time.

1.9 The redundancy

in electronic documents is higher than in paper documents

T here

are several levels of redundancy to electronic documents.

here

are several levels of redundancy to electronic documents.

Due

to the type of recording used for electronic data, minor errors in a

document can be corrected by existing tools. The tools rely on the

redundancy of checksums and other devices. MS Word tries to recover

defective documents.

Due

to frequent changes in documents, individuals learn to save previous

versions of the documents. Doing that generates redundancy of

document versions.

Emails,

flash memories, CDs all proliferate documents and result in high

redundancy. One copies documents to flash memory, attaches a

document to an email to a fellow worker or create a CD for

distribution or archiving.

Most

companies and many individuals backup documents regularly. Studies

show that “about 70% of enterprises meet

the criteria of verifying the integrity of their backup media at

least weekly.”

Tools

to control versioning of files create built-in redundancy wherever

they are applied. Versioning, i.e. version control,

widely used by the software industry has started to infiltrate word

processor as well as other applications. Versioning, by its very

definition maintains several versions.

1.10 Electronic

data is more likely to be created by several individuals than a paper

document

M

M S

Word supports “Document Collaboration.”

Where this term implies: “new objects, properties, and methods

of the Word 10.0 Object Library shown in this article allow you to

change the display of revisions and comments, accept and reject

revisions, and start and end a collaborative review cycle.”

S

Word supports “Document Collaboration.”

Where this term implies: “new objects, properties, and methods

of the Word 10.0 Object Library shown in this article allow you to

change the display of revisions and comments, accept and reject

revisions, and start and end a collaborative review cycle.”

Another

tool, Workshare 3,

is an add-on to Microsoft Word that manages collaboration on Word

documents and integrates this activity with email and the

organization’s document repository tool.

Collaborations

on databases (e.g. people using a bank’s ATMs update the bank’s

database), spreadsheets (e.g. BadBlue),

and Web sites are commonly practiced.

This

dwarfs collaborations on paper documents.

For

discovery it implies that the author of a Word document may not be

the only person involved in writing the document. One has to

determine all the parties that collaborated on the document.

1.11 Electronic

documents may be created by electronic means while paper documents

are created by humans

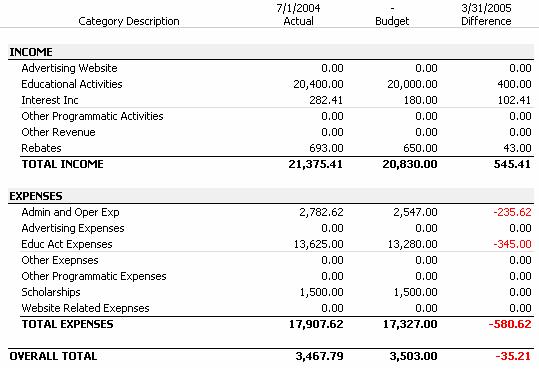

P aper

documents are always written by human beings. That is not necessarily

the case with electronic documents. We start with a simple, and

rather common, example. The Quicken financial program can generate

financial reports from a database of financial transactions.

aper

documents are always written by human beings. That is not necessarily

the case with electronic documents. We start with a simple, and

rather common, example. The Quicken financial program can generate

financial reports from a database of financial transactions.

This

is an application generated document.

Using

MS Word and its Autosummarize tool on a large document we got:

|

Patient

Monitoring Techniques in Telemedicine

Through

the leverage of these devices we can formulate distributed

algorithms and create effective data structures to properly

monitor patients. Every patient will have very specific needs and

we need a real time system to properly monitor the status of every

single patient.

Each individual patient will be uniquely identified with a

combination of building, floor, room, and patient id. Senior

Citizen Patients Monitoring Tree

Lastly,

each room contains one patient.

The

objects could be customized to contain all pertinent monitoring

information of each respective patient. Our goal is to formulate a

Medical Object Query Language (MOQL)

The medical

devices can interface with each object api to continuously update

each patient object (MP). Research Goals

|

The

tool created the document within the box. In this case, discovery has

to find the person that wrote the original document. That is not

necessary with paper document.

1.12

Electronic discovery requires support of an infrastructure that paper

discovery has never needed

T he

large volumes of data, its complexity, its variety of electronic

documents have brought about many types of computer tools to help

overcome the obvious difficulties.

he

large volumes of data, its complexity, its variety of electronic

documents have brought about many types of computer tools to help

overcome the obvious difficulties.

Socha

Consulting

provides the following entries in its Tools section (we drop the

commercial part and use just the generic description):

Electronic discovery software;

allows users to evaluate and manage electronic documents

Automated

litigation support software; allows users to organize, search, and

retrieve e-mail with attachments

Open,

view, print and convert various files types

Review,

acquire and analyze digital information on individual machines or

across a wide-area-network

View

and access contents of various file types

Automated

litigation support software; allows users to process electronic

files

1.13 Electronic documents are searchable while paper document

must be read

E

lectronic

documents benefit from a large variety of search tools. Search goes

through far more documents than human beings could review manually.

Different techniques provide a rich set of options starting from

keyword search, proximity search

and semantic searches.

For discovery, this search potential end up producing results.

lectronic

documents benefit from a large variety of search tools. Search goes

through far more documents than human beings could review manually.

Different techniques provide a rich set of options starting from

keyword search, proximity search

and semantic searches.

For discovery, this search potential end up producing results.

1.14

Electronic Document are Environment Dependent more than paper

documents

“ Electronic

data, unlike paper data, may be incomprehensible when separated from

its environment.”

The critical question is what is meant by environment. The report of

the Sedona Conference takes environment to be the actual software

structures used by the document. They say: “[i]f the raw data

(without the underlying structure) in a database is produced, it will

appear as merely a long list of undefined numbers. To make sense of

the data, a viewer needs the context that includes labels, columns,

report formats, and other information.” Actually, given just

the numbers from a paper ledger without the labels and tags is quite

meaningless as well.

Electronic

data, unlike paper data, may be incomprehensible when separated from

its environment.”

The critical question is what is meant by environment. The report of

the Sedona Conference takes environment to be the actual software

structures used by the document. They say: “[i]f the raw data

(without the underlying structure) in a database is produced, it will

appear as merely a long list of undefined numbers. To make sense of

the data, a viewer needs the context that includes labels, columns,

report formats, and other information.” Actually, given just

the numbers from a paper ledger without the labels and tags is quite

meaningless as well.

Environment

as in the folder in which a document resides can potentially

influence the document content. Some documents are made Lego style.

That is, the master document consists of independent sections, i.e.

small identifiable documents that are brought together by linking.

(Web pages tend to be thus constructed.) Once the master document

moves to another folder, the links, or some links, may be severed

resulting in a different document than intended.

Software

serves as a good example for environmental dependency of documents.

Paths, Include files and their location, location of executable files

are involved in developing and testing programs. If any one of the

elements is misplaced or wrong modified, the development process

suffers.

1.15

Legacy Electronic documents may be more difficult to discover

than Paper Documents

A bove,

we mentioned text documents written with WordStar.

Although organizations undergo migrations of applications, platforms,

methodologies and practices quite often, today’s technological

mind set mandates keeping electronic resources up to date or

ascertaining that tools to convert these resources from their old

form to the new form are readily available.

bove,

we mentioned text documents written with WordStar.

Although organizations undergo migrations of applications, platforms,

methodologies and practices quite often, today’s technological

mind set mandates keeping electronic resources up to date or

ascertaining that tools to convert these resources from their old

form to the new form are readily available.

The

danger to discovery due to migration is limited and typically

solvable. For instance, although WordStar documents may be 20 years

old, the marketplace provides tools to convert the document into the

latest MS Word version. After all, one can easily locate spare parts

for a 60s Beetle.

Discovery

does face difficulties due to old technology, but this stems mainly

from legacy systems.

Large organizations or companies with huge investments in information

technology found it too difficult to move on to newer technologies.

Thirty year old computer systems, though clearly archaic in

technological terms, are not uncommon. Discovery may have a handful

with such systems. Expert may be difficult to find, discovery tools

do not work on the legacy systems and, sometime almost unbelievable

yet true, even the owning organization does not really know much

about their system

(all they know is input and output). At the very least, discovery

will be expensive.

1.16 Multiplicity

of electronic documents tends to make assessing them more difficult

than paper documents

A claim is made that the ease and flexibility with which electronic

documents are created, copied, moved and managed tends to result in

too many copies of the document or pieces thereof. When one contrast

that reality to paper documents, without that ease and almost

costless space resources, it seems like moving from a disheveled

office to one neatly organized. Obviously, the mess is “not

good” for discovery.

claim is made that the ease and flexibility with which electronic

documents are created, copied, moved and managed tends to result in

too many copies of the document or pieces thereof. When one contrast

that reality to paper documents, without that ease and almost

costless space resources, it seems like moving from a disheveled

office to one neatly organized. Obviously, the mess is “not

good” for discovery.

Clearly,

this is a potential problem; we do not have research results that

help us know whether it is a problem or just an annoyance.

Multiplicity and disorder in document management is not the only

price an easy to use technology extracts. Following is a list of

difficulties we tend to encounter:

Use of sophisticated document

features backfires. For instance, word processors support use of

macros. (A macro is a series of commands that is recorded so it can

be executed later.) An uncontrolled use of macros may yield

unhealthy, shaky and difficult to use documents.

Documents may be part of a set

of document where the set has functional significance. Moving a file

away, i.e. deleting the document from the set, may damage the set.

For instance, a software product may come with a: installation

guide, user guide, reference guide and a demo scenario. Removing one

of these documents may make the product difficult to use.

Sets of documents may have

their members spread over a network of servers in diverse

geographical locations. A change in one of the locations may spell

trouble.

Collaboration in document

production and maintenance is typically encouraged. Yet,

collaboration has obvious pitfalls. Coordination, agreement,

accountability and scheduling are all supporting productivity and

source of complication

The

sky doesn’t get darker and electronic documents are not going

to be replaced by paper documents in the foreseeable future. Cars

kill more people than horses and buggy. We learned to enjoy the car

and never compare it to old animal technology. In summary, it’s

a problem but not a major one.

In

the chapter dedicated to ED tools, we will discuss tools in a generic

way and demonstrate their functionality.

his

point is obvious to the majority of observers. Today’s typical

disks are at several dozens gigabytes and these sizes grow

constantly. A typical medium-size company will have PC’s on the

desks of most white-collar workers, company-related data, accounting

and order information, personnel information, a potential for several

databases and company servers, an email server, backup tapes, etc.

his

point is obvious to the majority of observers. Today’s typical

disks are at several dozens gigabytes and these sizes grow

constantly. A typical medium-size company will have PC’s on the

desks of most white-collar workers, company-related data, accounting

and order information, personnel information, a potential for several

databases and company servers, an email server, backup tapes, etc.

Variety of electronic documents is larger than paper documents

Variety of electronic documents is larger than paper documents omputers

maintain information about your documents, referred to as “metadata,”

such as: author’s name, document creation date, date of it last

access, etc. A hard copy of the document does not reveal metadata,

although certain metadata items may be printed. Depending on what you

do with the document after opening it on your computer screen, the

actions taken may change the metadata collected about that document.

Paper documents were never that complex.

omputers

maintain information about your documents, referred to as “metadata,”

such as: author’s name, document creation date, date of it last

access, etc. A hard copy of the document does not reveal metadata,

although certain metadata items may be printed. Depending on what you

do with the document after opening it on your computer screen, the

actions taken may change the metadata collected about that document.

Paper documents were never that complex. ocument

efficiency is not a standard term. Here, Document Efficiency means

factors such as:

ocument

efficiency is not a standard term. Here, Document Efficiency means

factors such as: ocument

complexity is used quite widely in literature and industry. Recent

work deals mainly with XML documents that do not directly pertain to

this discussion. The presentation

ocument

complexity is used quite widely in literature and industry. Recent

work deals mainly with XML documents that do not directly pertain to

this discussion. The presentation aper

documents are easy to destroy. They may be throwing away, shredding,

burned, lost or stolen. Once such acts take place the documents

disappear. Deleting an electronic document eliminates only the

ubiquitous accessible copy. The document, i.e. its data, still exists

and in systems such as Windows and Mac OS, an accessible reference to

deleted documents may be in the trash bin. Restoring a document in

the trash bin, i.e. a deleted document, revives the document to its

original glory.

aper

documents are easy to destroy. They may be throwing away, shredding,

burned, lost or stolen. Once such acts take place the documents

disappear. Deleting an electronic document eliminates only the

ubiquitous accessible copy. The document, i.e. its data, still exists

and in systems such as Windows and Mac OS, an accessible reference to

deleted documents may be in the trash bin. Restoring a document in

the trash bin, i.e. a deleted document, revives the document to its

original glory.

hanges

to an electronic document are fast and easy. The reason is obvious;

all you need to do is make the change and save it. Changes to paper

documents, however, require retyping the whole document.

hanges

to an electronic document are fast and easy. The reason is obvious;

all you need to do is make the change and save it. Changes to paper

documents, however, require retyping the whole document. aper

deteriorates with time; paper documents can be destroyed by flood and

fire. Although these factors have their parallels in electronic

documents, e.g. a flooded computer loses its data; typical backups of

the documents practices maintain copies away from the “office.”

Paper documents may enjoy the same treatment, but the frequency,

extent and usage of such backups is substantially lower.

aper

deteriorates with time; paper documents can be destroyed by flood and

fire. Although these factors have their parallels in electronic

documents, e.g. a flooded computer loses its data; typical backups of

the documents practices maintain copies away from the “office.”

Paper documents may enjoy the same treatment, but the frequency,

extent and usage of such backups is substantially lower. here

are several levels of redundancy to electronic documents.

here

are several levels of redundancy to electronic documents.

aper

documents are always written by human beings. That is not necessarily

the case with electronic documents. We start with a simple, and

rather common, example. The Quicken financial program can generate

financial reports from a database of financial transactions.

aper

documents are always written by human beings. That is not necessarily

the case with electronic documents. We start with a simple, and

rather common, example. The Quicken financial program can generate

financial reports from a database of financial transactions.

he

large volumes of data, its complexity, its variety of electronic

documents have brought about many types of computer tools to help

overcome the obvious difficulties.

he

large volumes of data, its complexity, its variety of electronic

documents have brought about many types of computer tools to help

overcome the obvious difficulties.

lectronic

documents benefit from a large variety of search tools. Search goes

through far more documents than human beings could review manually.

Different techniques provide a rich set of options starting from

keyword search, proximity search

lectronic

documents benefit from a large variety of search tools. Search goes

through far more documents than human beings could review manually.

Different techniques provide a rich set of options starting from

keyword search, proximity search Electronic

data, unlike paper data, may be incomprehensible when separated from

its environment.”

Electronic

data, unlike paper data, may be incomprehensible when separated from

its environment.” bove,

we mentioned text documents written with WordStar

bove,

we mentioned text documents written with WordStar claim is made that the ease and flexibility with which electronic

documents are created, copied, moved and managed tends to result in

too many copies of the document or pieces thereof. When one contrast

that reality to paper documents, without that ease and almost

costless space resources, it seems like moving from a disheveled

office to one neatly organized. Obviously, the mess is “not

good” for discovery.

claim is made that the ease and flexibility with which electronic

documents are created, copied, moved and managed tends to result in

too many copies of the document or pieces thereof. When one contrast

that reality to paper documents, without that ease and almost

costless space resources, it seems like moving from a disheveled

office to one neatly organized. Obviously, the mess is “not

good” for discovery.